Absurd Jobs That Police Do That They Have No Business Doing

By:

The deaths of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile — two African-American men killed by cops early in July — intensified an already heated national conversation about police use of force and police reform, with many Black activists and thinkers challenging the role police play in our society.

Chicago-based activist Jessica Disu went so far as to tell FOX News, "We need to abolish the police, period." Activists like Disu are responding in part to the fact that police are increasingly being asked to take on duties that somebody else — or nobody — should handle.

Dallas police chief David Brown acknowledged, "We’re asking cops to do too much in this country," according to The Washington Post:

“We are. Every societal failure, we put it off on the cops to solve. Not enough mental health funding, let the cops handle it. ... Here in Dallas we got a loose dog problem; let’s have the cops chase loose dogs. Schools fail, let’s give it to the cops. ... That’s too much to ask. Policing was never meant to solve all those problems.”

Here are three absurd jobs that police have been given.

1. School Disciplinarian

The number of "school resource officers" has risen in recent decades amid concerns about mass shootings and other school safety issues, The Washington Post reported:

“But having officers present in classrooms and cafeterias has created its own set of concerns — about the criminalization of typical teenage misbehavior, about the discriminatory enforcement of vague laws, and about the excessive use of physical force against children in school spaces where they should be able to feel safe.”

A graphic October 2015 video showed a white police officer at Spring Valley High School in South Carolina putting a black girl in a headlock, flipping her out of her desk, and throwing her across a classroom. The girl, who allegedly used a cell phone against school rules, had reportedly disrupted class and refused to leave the room. In response, her teacher called for a police officer, not a counselor or therapist or teacher with whom she had rapport.

2. Police Misconduct Investigator

Can the police be trusted to police the police?

When officers are accused of misconduct, many police departments turn to an internal affairs unit to determine the guilt or innocence of an officer charged with wrongdoing. But there's an inherent conflict of interest in letting police departments investigate civilian allegations of their own officers' use of excessive force, unlawful arrest, and other misconduct, most police reformers argue. Another issue in many jurisdictions, such as New Jersey, is that internal affairs files are confidential because of state laws and police union contracts, meaning that there’s little transparency about how probes were conducted.

The federal government will step in when necessary to reform local police departments and often recommends establishing a civilian review board, an independent body that provides oversight of cops and sometimes has the power to investigate police misconduct. Reformers like such boards because they have no direct stake in the outcome of such investigations.

3. Mental Health Worker

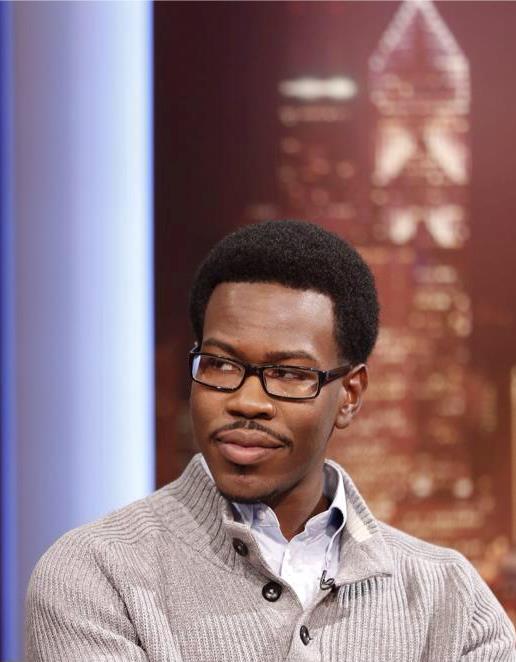

When police encounter mentally ill people, the outcome can be fatal, as demonstrated by examples like the case of Quentoni Legrier in Chicago.

Cops are typically first-responders in a mental health emergency, but most lack the specialized training necessary to identify symptoms of mental illness and to de-escalate potentially violent encounters involving mentally ill people. Ideally, mental health professionals would be dispatched to help people in mental crisis, not an armed government agent whose fundamental training is to enforce the law and exert command and control.

“Right now, we’re more willing to build prisons and jails than we are to provide services to people with mental illness,” Northwestern University mental health researcher Linda Teplin told the Chicago Reporter. “This disproportionately affects poor people and minorities and people who don’t have families who can help provide care.”

Police officer Michael Thomas Slager shot Walter Scott last April in North Charleston, S.C., as the Black man fled to avoid arrest for unpaid child support; The Atlantic's Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote afterward, "There is a tendency, when examining police shootings, to focus on tactics at the expense of strategy":

"We ask ourselves, 'Were they justified in shooting?' But, in this time of heightened concern around the policing, a more essential question might be, 'Were we justified in sending them?' At some point, Americans decided that the best answer to every social ill lay in the power of the criminal justice system. Vexing social problems — homelessness, drug use, the inability to support one's children, mental illness — are presently solved by sending in men and women who specialize in inspiring fear and ensuring compliance. Fear and compliance have their place, but it can't be every place."