Here's How Many People Can't Vote Because of Criminal Pasts

By:

On Friday, Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe (D) used an executive action to restore voting rights to more than 200,000 convicted felons.

.@GovernorVA signs executive action restoring voting and civil rights to over 200k Virginians pic.twitter.com/XUyEP0NoOn

— Terry McAuliffe (@GovernorVA) April 22, 2016

The move comes in time for the 2016 presidential election, which is significant in a swing state like Virginia, where 200,000 (or more) votes might swing the vote in a close race.

But just how much of an effect will re-enfranchised voters have on the election? Nate Cohn of the New York Times estimated that because ex-felons are disproportionately young and less educated, they're statistically less likely to vote than nonfelons. "[T]he electoral effect of felon re-enfranchisement is likely to be modest," he concludes.

But laws similar to Virginia's exist nationwide, and it's worth asking what electoral effect rolling back felony or criminal disenfranchisement laws could have more broadly.

So how many people can't vote in the U.S. because of felony convictions?

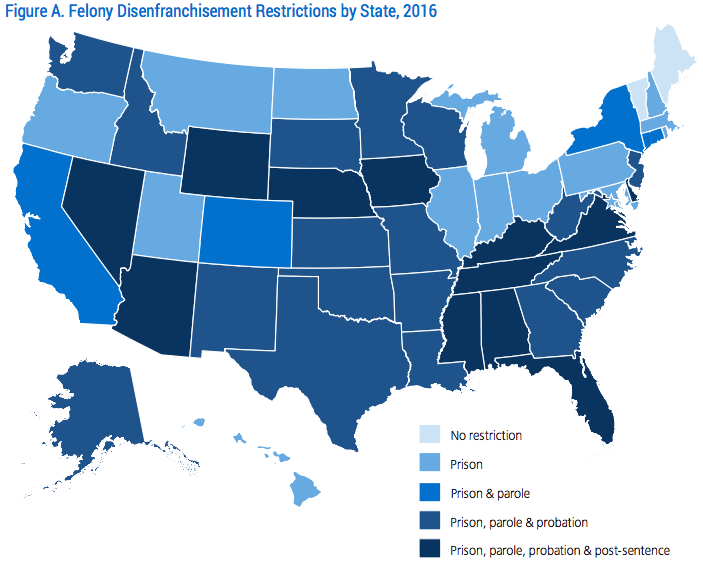

According to the Sentencing Project, some 5.8 million people are disenfranchised because of felony convictions. Just two states, Vermont and Maine, do not impose restrictions.

Sentencing Project - sentencingproject.org

Sentencing Project - sentencingproject.org

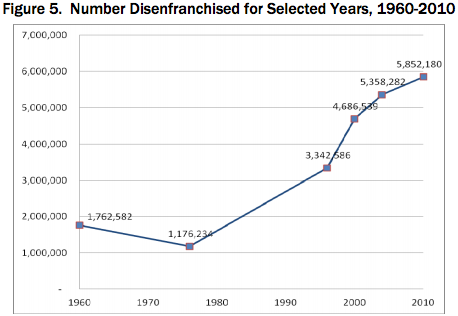

In pace with the explosion of incarceration rates in the U.S., beginning in the 1970s, the total number of disenfranchised voters has increased more than five-fold in recent decades.

Sentencing Project - sentencingproject.org

Sentencing Project - sentencingproject.org

What would that mean in an election?

It's obviously difficult to say just how re-enfranchised voters would influence the election. As Cohn points out, if previous research on the voting patterns of ex-felons provide any indication, those figures might be somewhat small, relatively: with some variance, about 20 percent of ex-felons generally turn out to vote. Of the 5.8 million people restricted by criminal pasts nationally, that would mean about 1,160,000 potential voters, which is significant considering that most of them would likely sway Democratic — based on previous trends, and the fact that felons are disproportionately minorities (who tend to register as Democrat).

More than 1.1 million votes is no small number in a national election. But more importantly, it's not a question of how felons might vote were they able to: It's that many of them can't in the first place. That's especially pertinent considering that felony disenfranchisement laws effectively suppresses the votes of millions of Americans, many of whom are disproportionately minorities.

"Because the racial disparities in the criminal justice system translate into higher rates of disenfranchisement, communities of color have their voting power diluted overall," Marc Mauer, executive director of the Sentencing Project told ATTN:. "Labeling formerly incarcerated people as second class citizens sends a message of exclusion that helps neither them or the larger community."