A Brain Expert Explains Why You Forgot What You Had for Dinner Last Week

By:

You probably remember what you had for breakfast, but can you remember what you had for dinner a week ago? The chances are you can't, and there are scientific reasons your brain chooses not to retain that kind of information.

Visual memory

One reason someone might not remember a minor thing they did a week ago is related to what's called "visual memory." Visual memory is a large part of how memories are processed (for people who can see), according to Scientific American.

Visual memory is how the brain processes images. This could be a house you've seen, a person's face, or a painting. How significant the image feels helps determine if the image is retained. You're more likely to remember the image of a beautiful sunset than that mediocre roast beef sandwich you had for lunch.

When someone's visual memory is processing something simple, like a meal, it stores that information in visual short-term memory. The brain prioritizes images and keeps them only as long as needed; in the case of lunch, it may determine that retaining the image is only important for the immediate future.

Flickr/Paul Yoakum - flickr.com

Flickr/Paul Yoakum - flickr.comPaying attention

There's more to it than that, though. "It boils down to a number of different things," Ziv Williams, an associate professor in neurosurgery at Harvard Medical School, told ATTN:. "The simplest thing ... is attention." If a memory is connected to a meaningful emotion — something "that's very fearful or something that's very emotionally salient, like love" — then the memory will stick more than if it isn't, Williams said.

You'd be more likely to remember eating that roast beef sandwich, or whatever it was, if you received an electric shock while you were eating. Without the electric shock, the memory doesn't have any visceral emotional connection.

Memories that aren't tied to a significant feeling or mental connection have to compete with the memories that are made later on.

"New memories are constantly interfering with [old memories], so that they're gradually wiping [them] out," Williams said. "Not completely erasing it, but basically using the circuitry or nerves that had originally been used for that memory."

Wikimedia/Henry Vandyke Carter - wikimedia.org

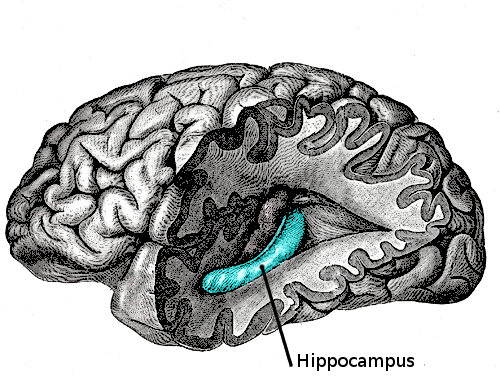

Wikimedia/Henry Vandyke Carter - wikimedia.orgThe hippocampus and types of memory

The part of the brain most commonly tied to memory is the hippocampus. The hippocampus plays a large role in creating memories as events occur. How a moment is processed initially can decide if the memory will remain. The hippocampus is also believed to put memories in context: drawing a connection between your first girlfriend or boyfriend and the smell of their perfume or cologne, for example.

The precise physical process that encodes memories is still up for debate. But the hippocampus has been found to be part of the process based on the fact that people with a damaged hippocampus may be unable to form new memories.

Not all memories are the same. "There are three general kinds of memories," Williams said:

- There's motor memory, also known as procedural memory, such as knowing how to ride a bike.

- There are declarative or semantic memories, such as recalling the president of the United States.

- "The third kind is called episodic memory, which is a little bit more autobiographical," Williams said. "It's basically what I ate for breakfast yesterday. These are kind of remembering things that happened to you in the past."

Flickr/Ian Armstrong - flickr.com

Flickr/Ian Armstrong - flickr.comNo one knows why, but some people have great episodic memory and others have great declarative memory, Williams said. One person might remember exactly what happened to them a few days ago, while another person may be better at recalling what they learned about World War II.

Why does the brain do this?

There may be an evolutionary reason that some memories stick and others fade away, Williams said. We have to go back to a time when humans were largely hunters and gatherers to understand why.

"If you ate something really bad that made you feel really sick, like a berry that made you very nauseous, you'd definitely remember," Williams said. "It's for evolutionary purposes, because obviously you don't want to keep eating the same poison berry."

The opposite is also true, Williams added. If an early human kept finding water or food in a certain area, she'd probably remember where for future reference. Since certain memories were connected to life or death scenarios, the brain evolved to give those memories greater emphasis.