The Serial Podcast Says A Lot About Our Generation's Trust in the Criminal Justice System

By:

The hit podcast Serial developed a fervent cult following for a narrative that weaves and meanders and stops and starts, and ultimately arrives at the conclusion that neither memory nor people can be completely trusted.

But Millennials didn’t need a podcast to tell you that.

According to Pew, only 19% of Millennials think most people can be trusted.

Older people are considerably more trusting. Pew found that 31% of Generation X, 37% of the Silent Generation, and 40% of Baby Boomers answered that most people can be trusted.

Over the course of the twelve-episode series -- the fastest to reach five million podcast downloads -- Serial’s host Sarah Koenig explores the elusiveness of memory and truth.

Serial asks its listeners to think about trust: who we trust, why we trust them, if we can ever really be sure that our trust hasn’t been misplaced. Koenig delves into the story of the 1999 Baltimore-area strangling of 18-year-old Hae Min Lee and the subsequent conviction and imprisonment of Lee’s ex-boyfriend, Adnan Syed.

Do you trust the criminal justice system?

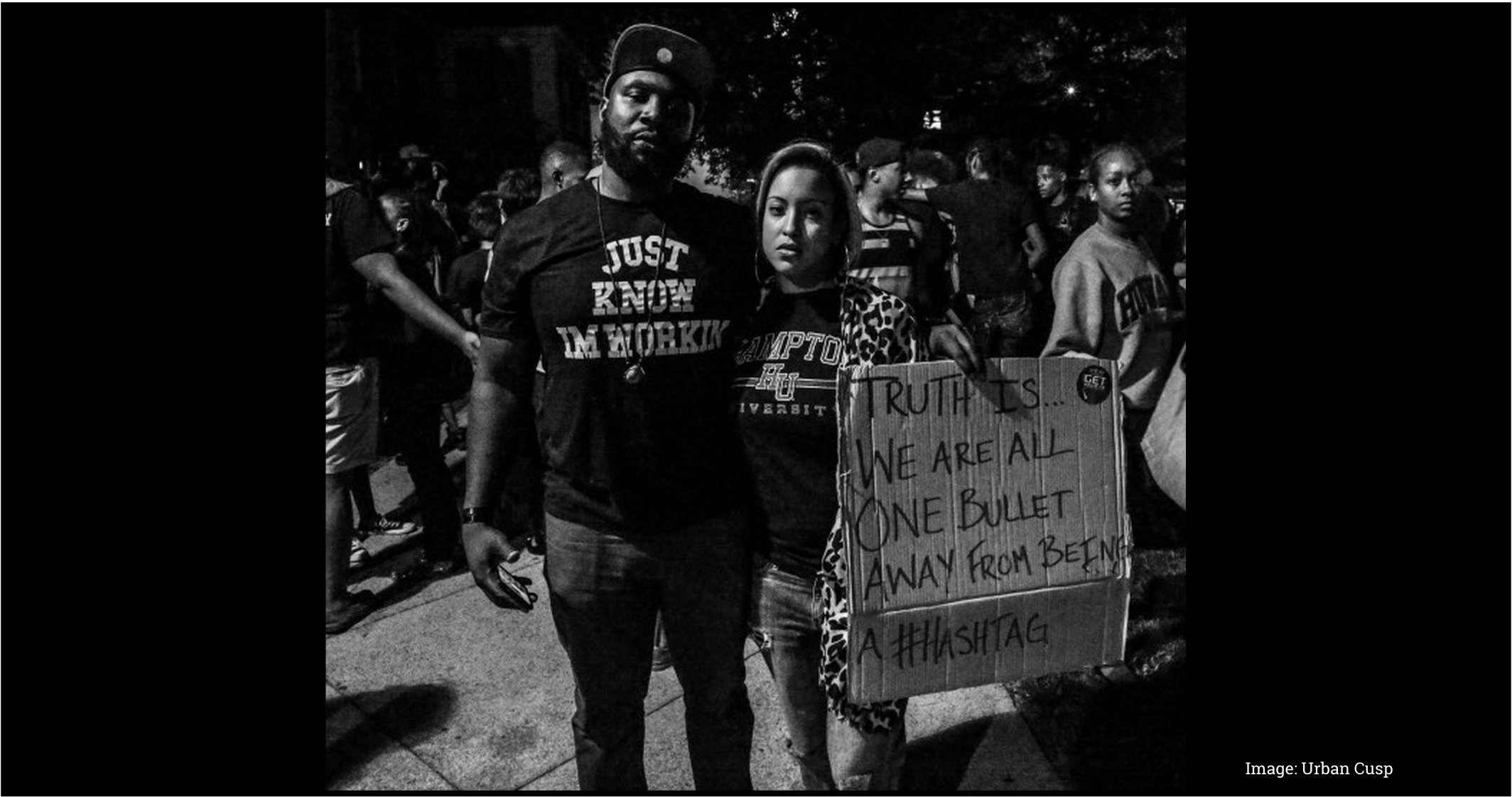

The questions that the podcast raises about the trustworthiness of the criminal justice system are similar to questions raised by the failure of grand juries to indict the officers who killed Michael Brown and Eric Garner. When the victim cannot tell his or her own story, who do we believe, and why? Do preconceived notions and prejudices about a race or a culture make this decision for us?

Serial asks if the criminal justice system failed Adnan. For instance, a would-be key witness for the defense was never called to testify. Then there was the prosecution paying for the lawyer of their only real witness, Jay, the witness whose testimony would put Syed behind bars for life. Jay also received a plea agreement that kept him out of jail. Can we trust Jay when he owes the prosecution for his lawyer and his freedom? But why should we trust Adnan instead?

Who do you believe?

Serial is really a battle between these two accounts -- Jay’s story is put up against Adnan’s throughout the series. The idea that truth is hidden somewhere between Jay’s and Adnan’s accounts of the case seems to be as frustrating to Koenig as it is to many listeners. The possibility that one or both young adults charged in a murder investigation would have lied in the interest of self-preservation isn’t surprising, but the podcast’s twelve episodes feature a myriad of people who don’t seem like they can be completely trusted either. Each episode of the podcast is brimming with potential ulterior motives, possible biases, and unanswered questions.

Are inconsistencies in people’s stories the result of not being trustworthy or do they come from an innocent, faulty memory? In fact, in one episode, Koenig illustrates just how tricky memory can be when she asks current high school students to account for their time during a day six weeks earlier -- just like Adnan was asked to do when he was first interviewed by police. Few can.

Is it easier to prove alibis in the age of smart phones and social media?

Adnan, Jay and their peers are the oldest of the Millennials, having been in the Class of 1999 in high school. They used pagers and email, but their technological footprint was considerably smaller compared to younger Millennials, those who are teenagers now. Today, memories can be recalled and refreshed by scrolling through Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter activity on a particular day.

But such publicly documented memories only tell part of the story. Pew also reported that 90% of Millennials say that people post too much personal information on the Internet. So, Millennials post more personal information than earlier generations had the capacity to, but they are also less trusting. Perhaps social media causes Millennials to be less trusting because social media profiles are often well-crafted to project a certain image, rather than a comprehensive, warts-and-all picture of a life.

When you can no longer manage your personal image.

Part of Koenig’s job was to resurrect the non-social media friendly teenaged versions of Adnan, Jay, and Hae.

“This search sometimes feels undignified on my part,” Koenig said in the first episode. “I've had to ask about teenagers' sex lives, where, how often, with whom, about notes they passed in class, about their drug habits, their relationships with their parents.”

In other words, things that today wouldn’t even be captured by social media.

Faced with subjects who didn’t always seem trustworthy and couldn’t always remember, Koenig exposed her own doubts and uncertainties to her listeners. She did her best to tell the story from the points of view of everyone involved. At least, every person who was willing and able to talk to her. Adnan’s mother and brother told the Baltimore Sun that the podcast had finally given them a chance to tell their story.

But whose narrative gets heard?

When it comes to murder, whether Hae Lee’s, Michael Brown’s or Eric Garner’s, the victim’s narrative inevitably disappears. All that we are left with is the narrative of the accused.

Each case makes us consider whether the system failed the victim. In the case of Michael’s Brown’s death, contradictory eyewitness testimony raised questions of the reliability of memory and the trustworthiness of bystanders, questions that weren’t asked in the death of Eric Garner since it was caught on video.

In Michael Brown’s death as in Eric Garner’s, the narrative of the white, male cop, the accused, prevailed over that of the black victim. With Hae’s 1999 murder, the narrative of the accused, a Pakistani male, has resurfaced fifteen years later. Adnan has had a second chance to tell his story, albeit in Koenig’s voice and this time to a much larger audience.

The questions Koenig raises about trust and memory, echo from the halls of Woodlawn High School in 1999 and reverberate through the streets of Ferguson and New York City today. If disenfranchised groups continue to struggle to claim a proportional share of the American narrative, it’s difficult to imagine that the next generation will be more trusting than Millennials are today.