Congressman Ted Deutch Has a Plan For Us to Get Serious About Mass Incarceration

By:

Congressman Ted Deutch (D-Fl.) wants to fix mass incarceration in America. And he thinks we can do it by creating a special, bipartisan commission of 14 experts on civil liberties, victims' rights, criminal justice, social services, and law enforcement. That commission would examine everything in our criminal justice system—from policing to trials to prisons—and recommend ways to help end mass incarceration.

We talked to the congressman about what exactly we could expect from this commission, which would be created by Deutch's recently introduced, bipartisan bill.

Editor's note: This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

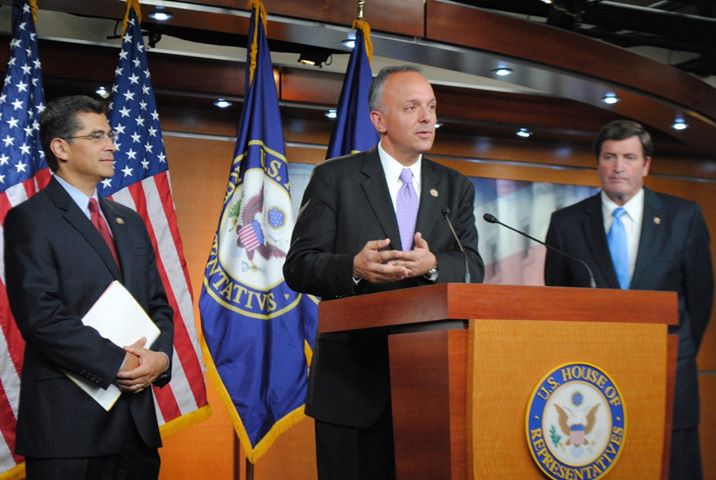

Congressman Deutch / Facebook - facebook.com

Congressman Deutch / Facebook - facebook.com

ATTN: Congressman, if you were running this criminal justice reform commission, what would you put on the agenda for the first day?

Congressman Deutch: There are some big picture points that I think everybody would have to have in mind as we start the process, starting with the fact that the United States, which is the leader of the free world, also leads the world in incarceration. And the statistics are really powerful—we have five percent of the global population, but 25 percent of the global prison population. That begs for a deeper analysis of the impact this has both on the 2.2 million people in jail and their families as well as the cost to taxpayers of over $80 billion a year. That number does not include the price paid by families and communities who are hurt by unnecessary jail time. That's the issue of mass incarceration, and all of that is really important.

The second issue is that too many Americans—when they get out of prison—are stripped of their voting rights, they're virtually unemployable, and that just perpetuates this cycle of hopelessness and poverty that too often just drives people back into illegal behavior. So, we have to deal with re-entry issues, we have to deal with the broader, societal issues of reiterating people coming out of prisons into our population.

And I would point out that as we start the conversation, it's a conversation, unlike most things these days, that is entirely bipartisan, both in the House and the Senate. There are all kinds of unlikely bedfellows who understand why it's important for us to take this up. The NAACP, the law enforcement groups, and the Koch brothers [are all in favor of reform]—this is not a typical coming together in Washington, and it shows that this is a really serious issue that deserves serious attention. We have not given it the kind of far-reaching analysis that it deserves in 50 years, and now is the time to do it.

ATTN: For as long as most Americans can remember, politicians who portrayed themselves as "tough on crime" usually had success in elections. What's changed in the last few years where it's become acceptable for elected officials to start talking about relaxing some of the tough laws that lead to mass incarceration?

I don't think that being tough on crime and respecting civil rights and human rights are mutually exclusive. I guess the thinking for some period of time was that they had to be. I think that from the recent tragedies in Ferguson, Staten Island, and Baltimore and [the resulting] calls for change, there are more people paying attention to these broader issues that aren't new, but were ignored for too long. There's a breakdown in trust in too many communities between law enforcement and the communities they serve. That's not good for the communities, and that's not good for law enforcement, who are doing very important, often dangerous work. That relationship has to be strong. The one statistic that jumped out for me is the fact that the FBI has never reported more than 460 fatal police shootings in a year. And so far in 2015, the Washington Post recently reported that there have been more than 500 just this year. [Editor's note: The Washington Post's count just crossed 600 on August 11, after this interview was conducted.]

The racial disparities within our criminal justice system are also becoming harder to ignore. Our drug policies have made it that Black men are 4 times more likely to be arrested for charges of marijuana possession. That's something that more and more people understand.

Another issue that I've really focused on is that a tiny fraction of criminal cases actually go to trial. There are too many poor defendants—too many poor, Black defendants—who don't get trial, they get a plea bargain. They'll often have a public defender who is overworked and hasn't had an opportunity to focus on the case. The defendant isn't really being represented in those situations.

So, all of that is coming together to spark an interest in doing something.

ATTN: Because much of this problem comes from state and local law and policing, what role does the federal government play?

Many of the "tough on crime" [laws] have come out of Washington, like mandatory minimums. [Those can be changed by the federal government.]

There are also federal grants from the Department of Justice where a tiny percentage goes to public defenders and well over 90 percent goes to prosecutors. The way those kinds of grants are administered and who gets them—a lot that comes from the federal government and it affects states and localities.

Is it time we reevaluated the federal programs that allow state and local law enforcement to acquire military-grade weapons and vehicles?

Yea, and I think there's growing support for that in Congress as well. We don't need a commission for that—Congress can do it—but when you have a collection of smart, dedicated people who really understand these issues and can sit around the table and talk about it, you can address that question. Whether the delivery of some of the most powerful weapons to our local governments is the best way to strengthen law enforcement and to keep those communities safe. That's exactly the kind of issue that this commission should discuss.

What about rescheduling marijuana? Would the commission discuss that issue?

I'm pretty confident that it would. If you look at the recent Supreme Court decision on marriage equality, that was so widely applauded, it's an example of an issue where the people of this country, young people in particular, were way out ahead of the politicians and spurred and contributed to that movement in a real and powerful way. And I am grateful for that. [Marijuana reform] is another one where the efforts around the country to pass laws and constitutional amendments and ballot initiatives to legalize medical marijuana—as was tried and efforts are underway to try again in Florida—is another issue where, I think, the people, and young people in particular, are out ahead of the people in Washington, D.C. There have been numerous reports of late that because of the scheduling of marijuana, we can't even do the research that is necessary to know how it can be helpful medically. You can put that into the broader debate about the way our drug laws are enforced and the broader picture of mass incarceration, and I think that would be ripe for some serious discussion.

ATTN: You briefly touched on public defenders. What are some ways to help our overworked public defenders so that defendants have a real defense?

I've introduced a bill called the National Right to Counsel Act that would make sure that every American's constitutional right of access to counsel is respected. There are a number of ways to do it. I already mentioned the Justice Department grants that wind up going to prosecutors instead of public defenders. The bill creates a center for right to counsel that would be modeled after legal aid on the civil side, but it would be established so they could come up with better practices, so that they can help those states who are falling behind. Just as we have legal aid, and we recognize that poor people should have access to our civil system, there's a constitutional right that needs to be upheld for everyone, and this Right to Counsel Center would help to ensure that it is.