Here's a Reason for Mass Incarceration That No One Talks About

By:

When judges and juries hand down their verdicts, the eventual release of convicted offenders is often determined by a judicial body that's entirely separate from the traditional courtroom and the final stage of criminal justice: the parole board.

There are more than 2 million adults behind bars in the U.S. today. Many lawmakers, including the president, have called for criminal justice reform. Ultimately, the aim of these reform measures would be to reduce the country's incarceration rate, which is the highest in the world, but in order to achieve that goal, it is going to take more than changes in mandatory sentencing, policing policy, and drug laws.

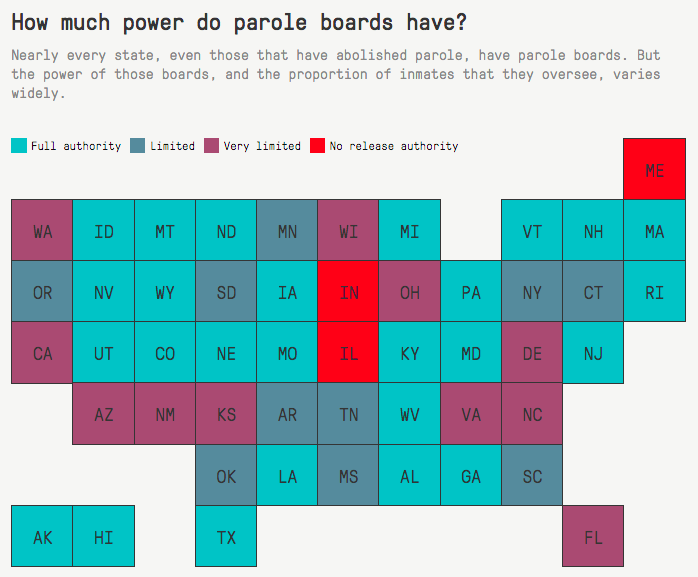

In at least 26 states, the fate of prisoners falls almost exclusively in the hands of parole boards, panels of people who choose whether or not offenders are released on parole after serving their minimum sentence. Elsewhere in the country, these boards exert a similarly omnipotent influence over the country's growing prison population, and the problems associated with this system of justice are many.

The Marshall Project - themarshallproject.org

The Marshall Project - themarshallproject.org

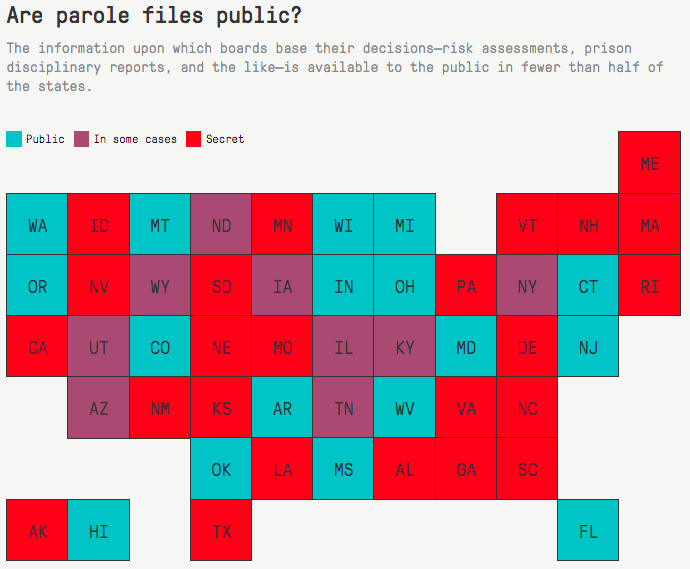

Parole boards are defined by secrecy; they lack oversight and transparency, in some states more than others. Indeed, "[f]ew others in the criminal justice system wield so much power with so few professional requirements and so little accountability," as the Marshall Project reported. In 44 states, the members of these panels are comprised of only those appointed by the governor, which has raised questions about the nature of these well-paid positions as well as the selection process.

"In many states, the boards' most basic workings are shielded by law from public view. Boards are not obligated to give any but the most cursory reasons for their decisions, which include not only whether to release prisoners but also how long they must wait to be considered again or what they can do to increase their chances in the meantime."

Fear motivates many parole board members to keep inmates locked up, even when they pose a low risk for future violence once they are released from prison. The question—"what if?"—prevents many from making reasoned judgments about the potential for recidivism, a prisoner's relapse into criminal behavior. Political pressure and media scrutiny also contribute to this fear; and since most panels do not have to answer to a higher power—not a court, judge, or independent oversight agency—the rationale of their decisions is often a peripheral concern.

A 2011 Stanford University study found that "the incidence of commission of serious crimes by recently released [inmates sentenced to life sentences] has been minuscule, and as compared to the larger inmate population, recidivism risk... is minimal." Of the 860 paroled murderers the researchers looked at, only five were sent back to prison, and none of those offenders went back for murder.

"Instead of acting as a release valve for our overstuffed prisons, parole boards too often act as a bottleneck," the Marshall Project's Beth Schwartzapfel told ATTN:. "There is no personal downside to board members who keep someone in prison, but the risk to their careers if they choose to release someone can be huge—even if that person never commits another crime."

The Marshall Project - themarshallproject.org

The Marshall Project - themarshallproject.org

The Marshall Project has been covering parole board issues as part of its ongoing mission to raise attention to the system's failings and spark a national conversation about criminal justice reform. Earlier this month, the nonprofit organization published an investigative feature titled "Life Without Parole," offering a comprehensive overview of the troubling trends that exist within parole boards across the country.

But their reporting hasn't ended yet; they have asked readers to help contribute to the investigation as well. In an effort to incorporate localized data into the organization's national story, they want the public to submit localized data collected from parole boards around the U.S.—the number of people eligible for parole, the number of people granted parole—so that everyone can understand the extent to which this institution influences the country's criminal justice system.

"Almost all of the data we have about parole boards is anecdotal," Schwartzapfel said. "We have some grant rate data that we were able to gather from various state boards, but each state collects this data in its own idiosyncratic way, and it's almost impossible to compare apples-to-apples with what we have."

"Is it true, as many in the field have told us, that grant rates remain historically low across the country, even as states are looking for answers to our mass incarceration problem? Some hard data will help us move toward answering that question."

So here's what you can do.

- Collect data. Check out your state's Department of Corrections or parole board website, look at the number of people eligible for parole as well as those granted parole, and report those figures here. If you can't find that information online, call and ask for it.

- Calculate the grant rate. That is, the percentage of eligible people that these boards have granted parole to in a given period. To do this, simply divide the numbers you collected in Step 1. There are some caveats to this process, however, so be sure to note things like word choice; there's a difference between offenders "considered" for parole and those that are "eligible," for example.

- Analyze the data. Don't trust that the information you've collected online is accurate or offers a complete picture of the parole board's activities. Contact the board's public information office and have them "pick the data apart."

- Find people on the ground. It's not enough to know the grant rate. Why were certain offenders released? Why were others denied parole? If you reach out to recently-paroled prisoners, attorneys with experience in the field, or prisoner advocacy groups, you'll probably get a better idea of how your state's board operates. And all of that data is important in constructing an in-depth narrative about the state of parole boards in America.

The Marshall Project has provided additional details about how to report localized data, but the most important thing to keep in mind is that any data helps. Whatever you can do to widen the scope of reporting on this subject contributes to a greater project, one that addresses the problem of mass incarceration in a way that few politicians have acknowledged. The secrecy of parole boards makes it difficult, but with more eyes on the ground, that veil falls apart.