Prison Justice Is An LGBT Rights Struggle

By:

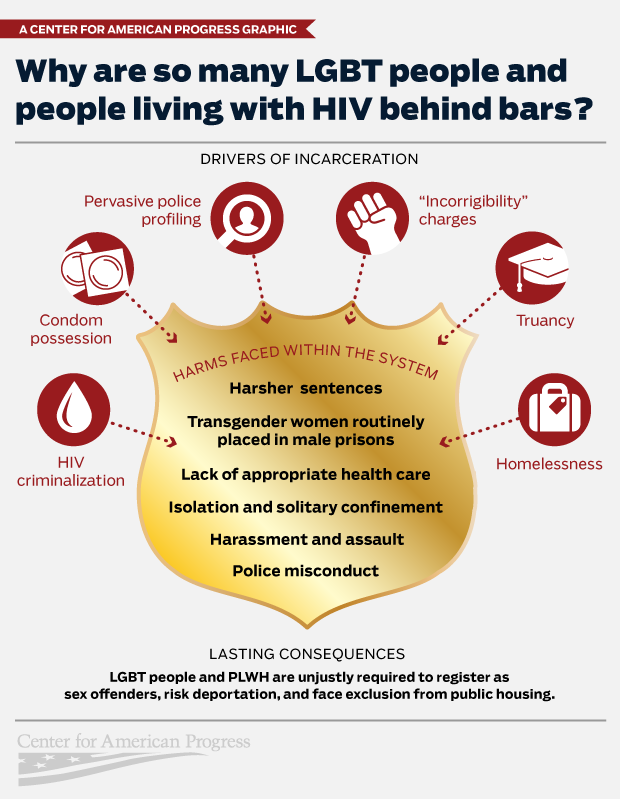

For the millions of LGBT people incarcerated each year, the sentence is only the beginning. Oftentimes, what happens behind bars is worse than what the state mandates.

Five percent of LGBT people in America have been incarcerated in the past five years. That rate is almost double the 2.7 percent incarceration rate for the general public and points to a major crisis in justice for LGBT people in the U.S. And within the LGBT community, certain groups remain particularly vulnerable.

A survey conducted by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian task force revealed that a whopping 16 percent of transgender people - and 47 percent of Black transgender people - have been incarcerated.

Lack of family support, homelessness, and social and economic discrimination - all issues that disproportionately oppress LGBT people - conspire to put LGBT people in conditions that often include physical and verbal aggression, and sexual abuse.

The effects of incarceration on this already-vulnerable population are devastating.

“From every angle, the justice system is broken for transgender and gender nonconforming people,” the authors of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey wrote in a 2011 report. “Instead of administering justice, it perpetrates injustice.”

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s 2009 Handbook on Prisoners With Special Needs puts it more bluntly: “Transgender and intersex (TGI) people experience extreme physical, sexual and emotional abuse and brutality while imprisoned,” the report says.

Police discrimination

The injustice that incarcerated LGBT people face starts before they enter police custody. Many LGBT people do not have trusting relationships with law enforcement, and according to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, as many as 22 percent of transgender people reported police harassment due to discrimination.

For LGBT people of color - and particularly Black and Latino transgender people - this risk skyrockets with 38 percent of Black transgender people report being harassed by the police.

6 percent of transgender people have been physically assaulted by the police; 2 percent have been sexually assaulted.

LGBT inmates are harassed and physically assaulted in prison

When incarcerated, LGBT people face anti-LGBT harassment and physical assault from other prisoners - and from the very guards charged with keeping them safe.

Transgender inmates are often classified and housed according to their assigned gender, rather than the gender with which they identify, making them particularly vulnerable to aggression from other inmates. Transgender women housed with men may be targeted for having feminine characteristics, while transgender men are often harassed and assaulted by guards.

In the National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 37 percent of transgender inmates reported harassment by prison guards themselves - with 44 to 56 percent of inmates of color having experienced harassment. The survey explained that 21 percent of incarcerated transgender women and 11 percent of incarcerated transgender men have been physically assaulted by other prisoners and staff.

LGBT inmates are shockingly vulnerable to sexual assault

The stereotype of a “predatory homosexual,” described as someone who rapes fellow inmates, continues to haunt our understanding of prison sexual assault. In reality, LGBT inmates are not more likely to commit sexual violence, but are more prone to experience it.

In the Bureau of Justice’s most recent report on sexual victimization in prison, 14 percent of gay, lesbian, and bisexual prisoners reported sexual assault, as compared to 3.1 percent of heterosexual prisoners. Transgender people are the most vulnerable, with 6 percent percent of transgender men and 20 percent of transgender women having suffered sexual assault while incarcerated; 38 percent of Black transgender women reported sexual assault.

LGBT inmates may be negligently - or even purposely - housed with other inmates who are known sexual aggressors, and guards often ignore victims’ reports. This means that men known to be gay or bisexual, as well as transgender women housed with men, are often targets of repeated sexual violence. In one study, 30 percent of gay and transgender inmates who reported violence were found to have experienced six or more sexual assaults. Victims sometimes resort to exchanging sex for protection from aggressors.

LGBT inmates are denied adequate healthcare

LGBT inmates are at a far higher risk than the general population of health concerns like mental illness and HIV - yet are routinely denied healthcare.

A Center for American Progress

A Center for American Progress

Among transgender inmates, according to the Transgender Discrimination Survey, 12 percent of transgender inmates are denied routine healthcare, while 17 percent are denied hormones.

The denial of condoms to inmates further exacerbates this lack of adequate healthcare, as sexual abuse makes LGBT inmates particularly vulnerable to contracting sexually transmitted dislike HIV.

This is in direct violation of United Nations Handbook recommendations that every person should have access to adequate healthcare, and that transgender inmates have the same, equal access to hormone therapy and gender reassignment surgery as non-inmates.

LGBT inmates are disproportionately placed in solitary confinement

Often, the only protection available to LGBT inmates is indistinguishable from punishment.

A dearth of safe facilities for LGBT people in prison means that sometimes, the only option to separate inmates from harassment, violence, and abuse is solitary confinement. Inmates may be kept in cells for 23 hours a day or more and cut off from access to recreational and education programming. The well-documented trauma of solitary confinement only exacerbates other health and safety concerns.

Ongoing solutions

The Yogyakarta Principles, written in 2006 in Yogyakarta, Indonesia, outline the application of International Human Rights Law for sexual orientation and gender identity. These principles not only outline a comprehensive vision of dignity for gender and sexual minorities; they also contain standards for fair treatment of LGBT inmates.

“Everyone deprived of liberty shall be treated with humanity and with respect for the inherent dignity of the human person,” reads Yogyakarta Principle 9. “Sexual orientation and gender identity are integral to each person’s dignity.”

A number of researchers and world leaders, from Columbia University to the United Nations, have urged government reform of prisons in accordance with these principles.

Recently, some U.S. government agencies have moved toward change. In 2012, the U.S. Department of Justice approved the Prison Rape Elimination Act, a federal law that targets prison sexual abuse. Meanwhile, Dallas, Denver, Los Angeles, and Washington D.C. prison systems have implemented far-reaching reforms.

Some of the recommendations include:

- Housing according to gender identity. Housing transgender people according to their gender identity, rather than their assigned gender, not only affords transgender inmates protection from physical and sexual assault, but it affirms the dignity of transgender inmates’ identity and expression.

- Staff training. Often, prison staff aggress upon, rather than protect, inmates under their care. Recommendations call for active recruitment and inclusion of LGBT staff to work with vulnerable populations, and rigorous gender and sexuality training for all prison staff.

- Safe housing for LGBT inmates

- Non-custodial measures and sanctions

The UN and Columbia reports both call for attention to individual safety when assigning housing to LGBT inmates, with the option allowing LGBT inmates to be away from the general population. A final suggestion to improve LGBT incarceration: Stop incarcerating LGBT people, instead, assign them to non-custodial sentencing.

“The extremely vulnerable status of LGBT persons in almost all prison systems may amount to their sentence being transformed into a much harsher punishment than that handed down by the courts, thereby justifying a degree of positive discrimination during sentencing,” according to the Handbook on Prisoners with Special Needs, suggesting that, whenever possible, governments seek non-custodial sentencing options.