Here's How Science Can Wrongfully Convict Someone

By:

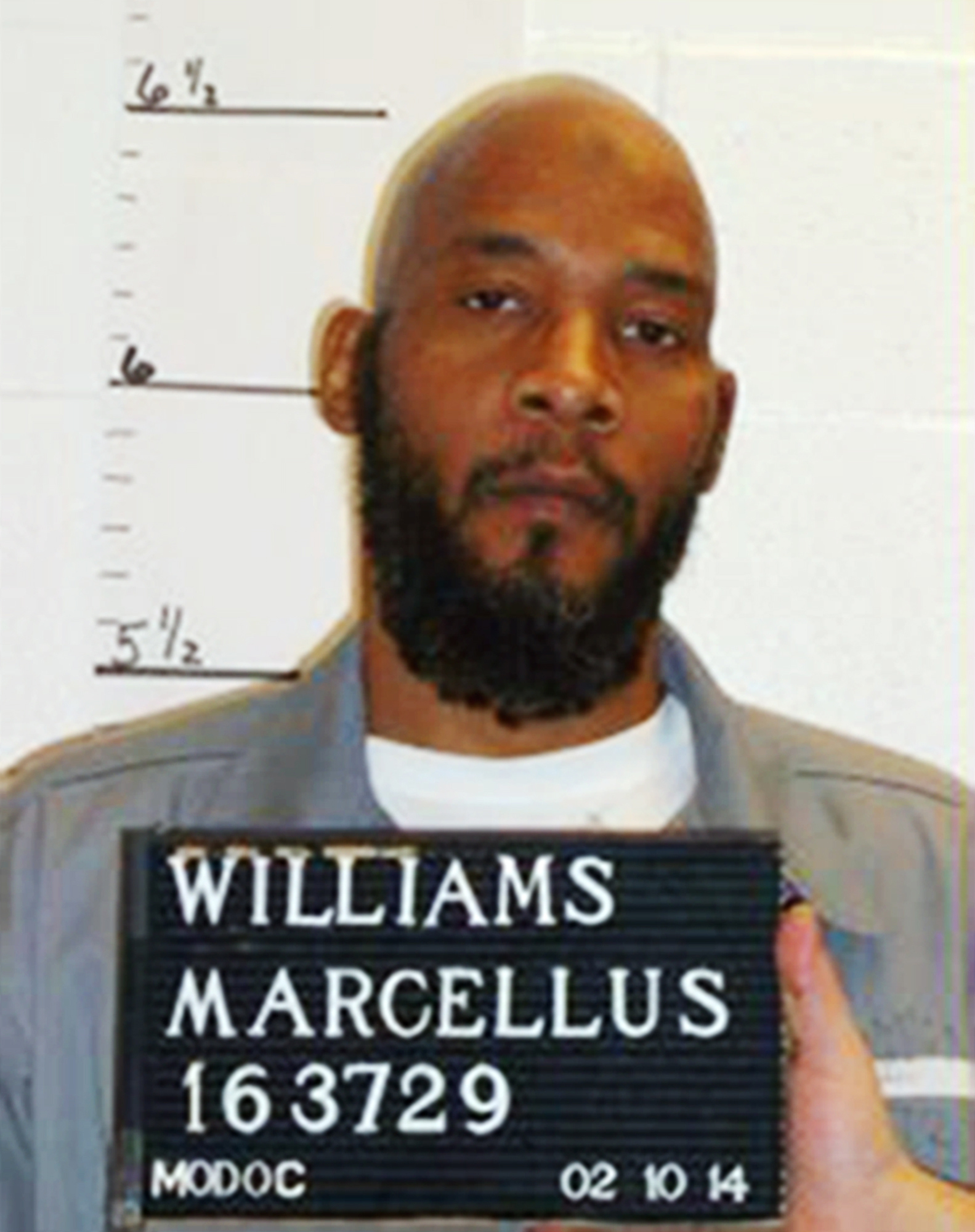

Marcellus Williams, who was convicted of murder 17 years ago, is alive on Wednesday morning thanks to recently uncovered DNA evidence.

Missouri Department of Corrections via AP, File - apimages.com

Missouri Department of Corrections via AP, File - apimages.com

Missouri Gov. Eric Greitens ordered a last minute stay of execution for Williams, 48, on Tuesday evening, so that a newly created board of inquiry can evaluate forensic evidence that the defense says proves their client's innocence.

Williams' conviction highlights the controversy surrounding forensic evidence.

Williams was convicted in 2001 of the 1998 slaying of Felicia Gayle, 42, a former reporter for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. During the trial, prosecutors pointed to several key pieces of evidence that they claimed was proof that Williams was the killer, including possessions belonging to the victim that were allegedly found in his car and the fact that a laptop belonging to Gayle's husband was sold by Williams.

"Based on the other, non-DNA, evidence in this case, our office is confident in Marcellus Williams' guilt," Loree Anne Paradise, deputy chief of staff for state Attorney General Josh Hawley told CNN.

However, Williams' defense team has seized upon newly acquired evidence that shows that his DNA wasn't found on the murder weapon, and that hair samples and footprints found at the scene don't trace back to him either.

But DNA evidence isn't foolproof. In April, Massachusetts, prosecutors dismissed 21,587 cases because a chemist named Annie Dookhan faked results to save time and increase her productivity. And even when scientists are well-intentioned, there is still subjective interpretation and controversial science being used as legal evidence in some courtrooms.

So, how trustworthy is DNA evidence? And are the courts evolving fast enough to make use of the best evidence available? ATTN: talked to Josh Tepfer, an attorney at the University of Chicago Law School's Exoneration Project, about faulty evidence in the criminal justice system.

Exoneration Project - facebook.com

Exoneration Project - facebook.com

ATTN: Is faulty evidence and bad testing a significant factor in wrongful convictions?

Tepfer: It's a huge factor in wrongful convictions. It involves humans doing testing. In Massachusetts recently, 21,000 convictions were overturned because of the misconduct of a lab analyst. The second way it's a problem is that as evidence and scientific standards continue to improve [it] demonstrates that [...] 'impression evidence' that we've long relied on isn't as reliable.

.jpg?auto=format&crop=faces&fit=crop&q=60&w=736&ixlib=js-1.1.0) Jim Watson/Wikimedia - wikimedia.org

Jim Watson/Wikimedia - wikimedia.org

ATTN: Can you explain what impression evidence is?

Tepfer: Impression evidence is categories of evidence like fingerprints, bullet comparisons, bite marks, and things along those lines. For a long time, people would say, "only this individual could leave this bite mark because the teeth are so unique" or they would say that this particular physical evidence was a match, when it really isn't really a match. There can be similar characteristics, but you can never really say with scientific certainty that there is a unique match to certain individuals. What we saw for many, many years is putting on [the witness stand] a forensic odontologist who would testify that "I took a mold to someone's teeth and I took a mold of someone's skin with teeth marks and I can say with certainly that this person bit them." We know they've been wrong because DNA testing will later prove it, but even more interestingly we've seen examples where a bite mark wasn't even a bite at all. With hair comparison, even blood tests where they determined a match and it was validated at the time by the scientific community, you go back and then use updated forensic tests and it wasn't a match, or it wasn't blood at all but it was paint. Or it wasn't even human hair but animal hair or maybe not the same hair.

Danielle DeCourcey

Danielle DeCourcey

ATTN: So why was this allowed into court in the first place?

Tepfer: People were trained on the scientific principles at the time. They were saying things they believed to be true at the time, that turned out not to be true. You even see it in medical testimony, like in shaken baby syndrome cases. A series of doctors testify that injuries are unique and can only be caused shaking a baby, but there's no sign of abuse. They might say they know the damage happened right away, but there's a number of diseases or accidental falls that could cause the exact same type of brain injuries where it doesn't show up right away. What we're seeing is a lot of blue ribbon studies like the President's Council [President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology] report talking about all of these flaws. The reaction from the criminal justice community has been non-existent. They're not applying scientific advances to new cases.

ATTN: The average person hearing this would probably be shocked to learn that there could be problems with the forensic science they see used in courtroom dramas. I assume that there could be people incarcerated right now who were wrongfully convicted with faulty science. How are we working to fix these convictions?

Tepfer: They're being overturned one at a time, when an individual is lucky enough to get counsel to advocate for those cases. Even with the forensic odontologists, many of them have now admitted that they largely overstated their previous testimony. You would think the reaction would be, "Oh my god, what case did this come up in? What cases did they testify in?" You would think they would want to go back and find out. If an officer was caught framing people, there would be a mass review. These types of mass reviews, like in Massachusetts, are extraordinarily rare. If a plane crashed, you would go back and examine it to find out how [it happened]. You [would] put together committees and you make sure you correct this. That never happens either. When you have something like a wrongful conviction, when someone is on death row or someone has been in prison for a long time, there's a duty to find out what went wrong. Unfortunately, that is a giant vacant abyss in the criminal justice system.

ATTN: Why is there a reluctance to address previous convictions that could be based on faulty science?

Tepfer: It takes a lot of time and it takes a lot of effort and it takes a lot of resources, and those things are scarce in the criminal justice system. It's an overburdened system on all levels, and we have too many cases to prosecute and investigate looking forward. The lowest thought for anyone involved is to go back and re-examine ones that are already closed. Of course, it's extremely important for the individuals affected. It's extraordinarily important.

Bart Everson - flickr.com

Bart Everson - flickr.com

ATTN: Is there any standard system for evaluating what kinds of scientific evidence is allowed or is that up to the discretion of the judge?

Tepfer: The judges are gatekeepers and part of their role —depending on the jurisdiction— is to only allow juries to hear about proper scientific techniques. The problem is the legal system is based on precedent. Science, of course, is not based on precedent and it's always improving. With fingerprints, everyone just assumes that they're right, but we see more and more examples of fingerprints being incorrect. It doesn't mean the whole thing needs to be thrown out, but we need to have reliability hearings. It should have to be reevaluated based on these new studies. But routinely, no one is conducting these types of reliability hearings. Everyone talks about fingerprint testing and how long it's been introduced in trials.

ATTN: Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced in April that the Department of Justice will no longer fund the National Commission on Forensic Science. What does that mean for the criminal justice system on the national level?

Tepfer: The idea that the sky is falling is a little disingenuous. Under Obama, the Department of Justice, didn't implement the findings of the President's Council [of Advisors on Science and Technology]. They continued to make statements that they didn't agree with the findings and they were going to continue to use bite mark evidence. The Trump Administration's not the only one at fault.