Researchers Made a Huge Discovery About Human Evolution

By:

A recent discovery in Morocco has upended decades of previous conclusions about human evolution.

For the past 50 years, researchers had conclusively traced the origin of humankind to East Africa and—after a series of revelations culminating in 2005—it was determined that the oldest known human bones dated back to around 200,000 years ago.

But a new study published in the journal Nature details the findings from a decade-long excavation that yielded a collection of human bones. After dating the bones, researchers determined that humans evolved a whopping 100,000 years earlier then the previous estimate. And given the location of the bones, human evolution was clearly occurring across all of Africa, not exclusively in the eastern part of the continent.

Nature - nature.com

Nature - nature.com

"Until now, the common wisdom was that our species emerged probably rather quickly somewhere in a 'Garden of Eden' that was located most likely in sub-Saharan Africa," Jean-Jacques Hublin, one of the study's authors, said in a press release. "I would say the Garden of Eden in Africa is probably Africa—and it's a big, big garden."

The discovery also offers new information about evolutionary development.

In addition to dramatically changing previous theories of when and where humankind began, the discovery also offered a new understanding about the anatomical development of Homo sapiens.

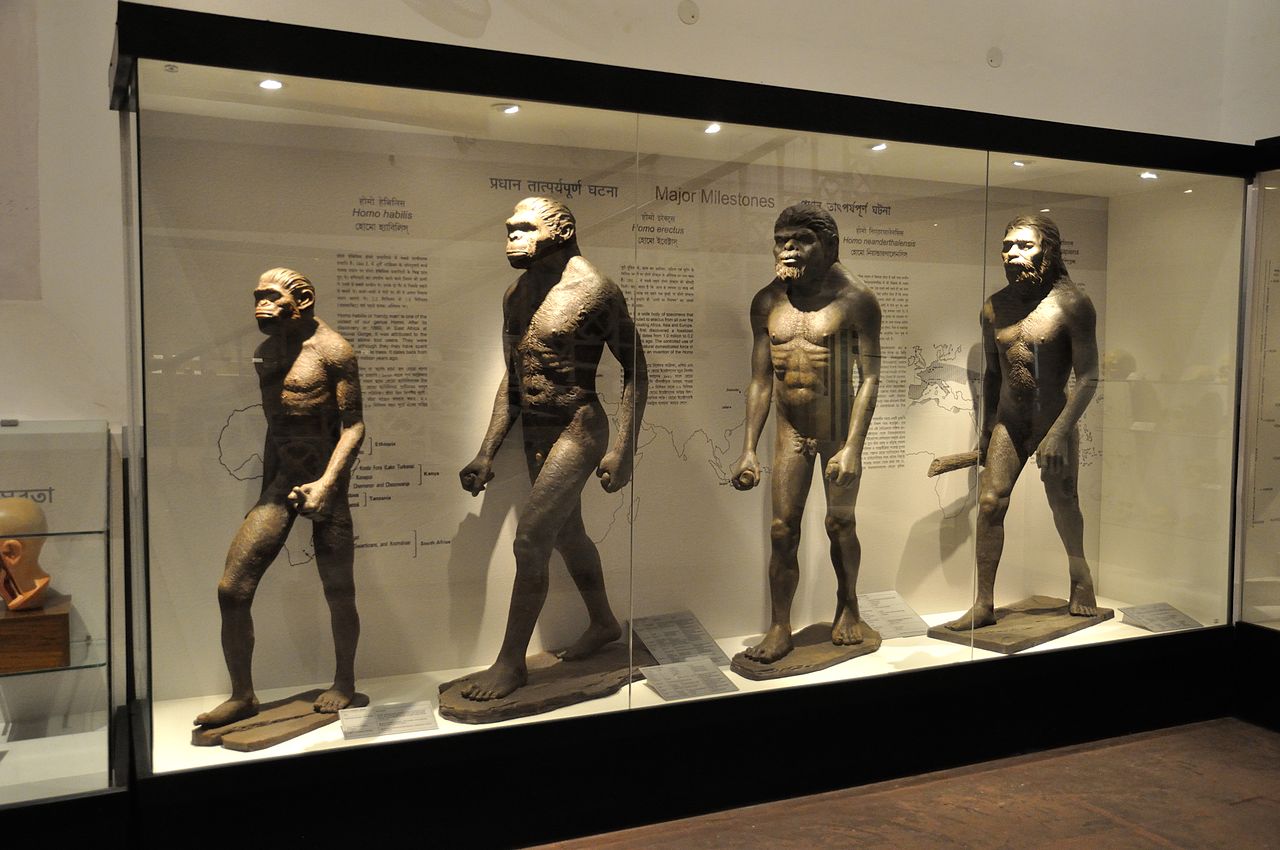

You'll notice in this image, for example, that the oldest humans (left) had elongated craniums compared to modern day humans (right).

.jpg?auto=format&crop=faces&fit=crop&q=60&w=736&ixlib=js-1.1.0) Nature - nature.com

Nature - nature.com

As the Nature study posits, given the other structural similarities of these bones, it's possible to conclude that cranium size was one of the last anatomical features to evolve—in this case, condensing as the brain became more complex and connected—in humans.

But not everyone is convinced that the bones discovered in Morocco should be classified as Homo sapiens.

Rick Potts, a paleoanthropologist at the Smithsonian's Museum of Natural History, said the skull's elongated cranium and other facial features suggest that the species is too primitive to be considered a modern human. However, he said that doesn't detract from the discovery's significance. As he told NPR, these "new finds from Morocco are a kind of snapshot in that whole process of transition from archaic to us."