The Truth About Lies and the Human Brain

By:

Truth was a particularly hot topic during the 2016 presidential election.

.jpg?auto=format&crop=faces&fit=crop&q=60&w=736&ixlib=js-1.1.0) YouTube/Perfection Imparfaite - youtube.com

YouTube/Perfection Imparfaite - youtube.com

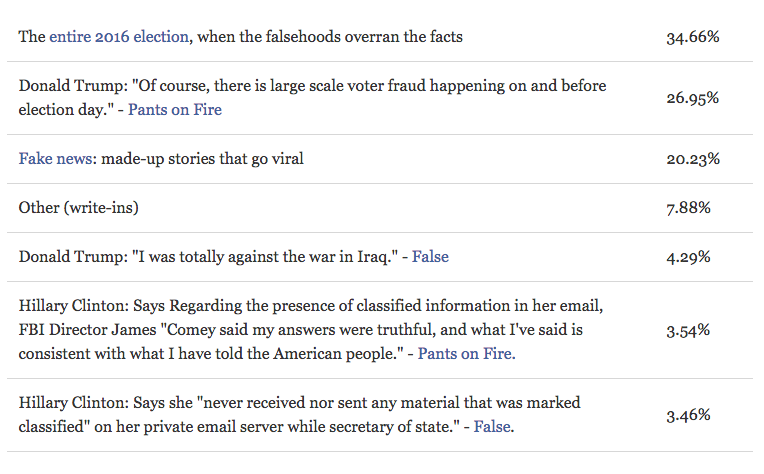

Fact-checking dominated presidential debate coverage, and news outlets and technology companies addressed the circulation of fake news following the election.

Apparently, people even felt deceived by the political process. Politifact readers crowned the election the biggest "Lie of the Year" in a December poll.

Politifact - politifact.com

Politifact - politifact.com

It's impossible to determine exactly how many votes were influenced by lies told by politicians and/or scam news stories, but psychological and neuroscientific research provides insight into how they may have shaped voter behavior.

Part of the reason we can't determine how much lies shaped election results is due to the unconscious biases that contribute to decisions we make. Researchers theorize that people may make major choices based on these biases, which can be informed by things we rationally know to be untrue.

ATTN: spoke to Uri Maoz, Ph.D., a cognitive psychology and behavioral neuroscience professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, about what brain science can tell us about the role of lies in politics and the 2016 presidential election.

We aren't aware of everything that shapes political decisions.

"There are two aspects to political decisions," Maoz explained. "They're probably not as robust or as grand and overarching our entire value system as we sometimes think. And even small things like some kind of neural bias can sometimes change these potentially important decisions."

In other words, we typically think we participate in the political process by weighing our values carefully and making rational decisions. But we also take subconscious preferences into consideration. By definition, we don't know what these are or when they are the deciding factor that determines who or what we vote for.

Scientists attribute subconscious psychological beliefs to "neural bias" or "biased neurons." These determine things like which hand you use and if you prefer immediate gratification, Maoz explained. In a 2011 paper (PDF), Kathy Bobula, Ph.D., said we are born with neural biases to prefer people we perceive as similar to ourselves.

These unconscious biases can be impacted by lies and shape human and animal behavior.

Maoz and his research team reviewed an experiment where monkeys chose between getting more juice later or a smaller portion immediately. The results provide a theory of how unconscious bias could determine large decisions people make.

"When the difference in the reward is so large, the biased neurons aren't going to make a difference," he said. However, when they looked at the margin of error, monkeys that chose significantly smaller rewards had atypically high bias activity, which the researchers linked to their decisions differing from the other monkeys.

"[Difficult, large] decisions may well end up being considerably influenced by neural biases that are not part of the rational decision process and start before rational deliberation can even begin," Maoz and his co-authors conclude.

It's not that we don't consider the options when we make choices, but rather that we go into the process "skewed" by unconscious biases.

Difficult decisions involve options that appear relatively equally desirable (or undesirable). So when you're making a choice and practical pros and cons even out, you may not be aware of what tips you over the edge. And large decisions (moving, taking or leaving a job, buying a home, etc.) tend to be difficult.

aboutmodafinil.com - flickr.com

aboutmodafinil.com - flickr.com

"Going back to the election, it could be small things like a fake news story or some lesser or more blatant lie that was told could have just tipped the scales," Maoz said.

When people make decisions based on unconscious biases, they can come up with — and believe — compelling, rational explanations for their behavior.

"When you're asking why people believe these lies, I'm not even sure if you would ask the person 'do you believe this lie?' they would say, 'Oh yeah, sure.' Like the Pizzagate thing," Maoz said. "Most people would say it sounds kind of ludicrous. But still when they go and cast their ballots, they might have this small potentially unconscious influence that's enough to tip the scales."

AP/Darron Cummings - apimages.com

AP/Darron Cummings - apimages.com

If a fake news story influenced someone's vote on an unconscious level, they would believe something else changed their mind.

"If something tips the point and you're now going for candidate A rather than candidate B, and you ask yourself why you're doing that you're going to give yourself an answer," Maoz explained. "But it could well be that there is some kind of unconscious influence that made you waver."

"People are very good at giving convincing answers to difficult questions," he said

Neural bias impacts people "on the fence."

This bias wouldn't impact polarized voters, but if someone was torn between two candidates — as many may have been this year, when two historically unfavorable presidential hopefuls faced off, it might. Trump's upset victory hinged on narrow margins of voters in swing states, as the Washington Post reports. Though Trump's win defied almost all pollsters projections, polls reported high estimates of undecided voters throughout the race.

"If they're kind of wavering there, then it could, and it seems that in these elections that might have had a significant effect," Maoz said.

AP/Jim Cole, AP/Charlie Neibergall - apimages.com

AP/Jim Cole, AP/Charlie Neibergall - apimages.com

Researchers are still investigating where brain science meets other forces that shape decisions and politics.

"On one hand, there are very complex political reasons [for political movements] in the U.S. and in Britain and in Italy and other places around the world," he said. "On the other hand, you have all these unconscious influences, and where they connect exactly we don't well enough."