Woman's Story Reveals How Anti-Trans Discrimination Can Be Legal

By:

A federal judge's Thursday ruling over the firing of a transgender woman from a Detroit funeral home has sounded alarms about the legal loopholes in laws prohibiting anti-LGBT discrimination.

The EEOC, who brought the lawsuit, claimed that the 2013 firing of transgender woman Aimee Stephens — who told her employer she was transitioning and therefore would no longer abide by the funeral home's dresscode for men — violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which says that employers can't discriminate against employees based on gender stereotypes, the Huffington Post explains.

Stephens' employer, RG & GR Harris Funeral Homes Inc., said they had a right to fire her because their business was tied to their Christian faith. The court ruled in favor of Harris.

In order to better understand the decision, ATTN: spoke to Lambda Senior Counsel and Director Jennifer C. Pizer. Though Pizer said the decision would likely be appealed, she also took a deep dive into the court's arguments and explained why she took issue with the ruling.

ATTN: Has Lambda been involved with the Detroit funeral home case?

Jennifer Pizer: This is a case we knew about and were following closely. It was brought by the EEOC, and they have been doing some high profile very important work clarifying the federal employment protections that LGBT people have and educating the general public about that.

This was a case we knew was pending and were anticipating the decision, and I will say we’re tremendously disappointed at the result. We think it's incorrect on multiple points. It's correct on a couple of points, but it's incorrect in our view in a couple of important ways.

ATTN: What do you think the decision got right?

JP: One of the important issues that, in my view, the decision gets correct is that the judge rejected one of the arguments made by the employer, the funeral home.

The argument was made that the ban on sex discrimination that's a part of Title VII allows employers to have gender specific differentiated dress and grooming standards, and its not sex discrimination to require men to adhere to the standards for men and women to adhere to the standards for women.

One of the issues in the case was that the plaintiff, the employee informed the boss that she was coming out as a transgender woman and under doctors orders, she was required before undergoing the medical treatment to transition physically she needed to live in the gender consistent with her gender identity. The boss responded 'you can't do that and if you are going to insist on doing that you're employment here has ended,' and she was fired.

So the employer, the funeral home was relying on a 2006 case decided by the federal court of appeals out here on the West Coast, Jespersen v. Harrah's Casino. It's a case I'm very familiar with because I represented Darlene Jespersen [who sued her employer, Harrah's casino for firing her for not wearing make-up required by a dress code] in that case.

The ninth circuit rejected the claim we were making on behalf of Darlene Jespersen, but said employers are not permitted to impose sex stereotypes on workers and if the dress or grooming standards involve burdens of sex stereotypes then the plaintiff can have a claim. So that was an important ruling even though the court did not allow my client to use the ruling.

With the funeral home, this trial judge said if we look at the law in the federal circuit that applies here in Michigan — the sixth circuit court of appeals — we have strong law that employers may not employ sex stereotypes or treat employees differently based on sex stereotypes.

The employer here was not allowed to rely on this Jespersen ruling. So that was I think correct, but the decision is confused about many different issues.

ATTN: What did the decision get wrong?

JP: Even in understanding the dress code rule correctly, I think the court was confused about the idea of who this plaintiff is. If she's a transgender woman, she should be able to dress consistently with the rules that apply to women.

The court has this whole discussion later in the opinion that sort of misses the point and says 'well, if the EEOC wants to fight discrimination that's based on gender and gender stereotypes, then they should be attacking the whole idea of a gender differentiated dresscode, and they're not doing that, so they must really not be sincere about being concerned about this particular kind of sex discrimination, because they're fighting to allow this worker to wear female attire and according to this court, they're fighting to let this person conform to a sex stereotype, so they can't be sincere about sex discrimination.

That's not how it works. The idea is you don’t judge an individual based on conformity or nonconformity or partial conformity with somebody's gender stereotype. You treat the individual as an individual, and on the quality of their work.

That's night and day different from saying 'we must abolish all rules or policies that build into them something different for women and for men and we must require that everybody dress the same, and everybody look the same.' That’s sort of turning the rule on its head. The rule is about protecting individuals, it's not about requiring conformity. It's requiring room for diversity.

This confusion came up in the second part of the decision, which was about the employer's other main defense argument, which was a demand for special religious exemption from the Title VII rule that otherwise would apply.

The big news of this decision was that court agreed that this for profit business has a right to make freedom of religion arguments under the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and that that religious argument carries the day, and the worker loses.

ATTN: How was the Religious Freedom Restoration Act used in this case?

The way the argument is presented in this case is profoundly alarming if you think about how it played out here and how it could play out everywhere if courts were to accept this reasoning.

This was a court relying on the Supreme Court’s Hobby Lobby decision of a couple of years ago. Some of us sounded alarms when Hobby Lobby came down worrying about exactly this kind of application of Hobby Lobby.

In Hobby Lobby and in this case, an employer was sued for not doing something that federal law said the employer was supposed to do. In Hobby Lobby they were supposed to include insurance coverage for birth control within the employee health plan. In this case, Title VII would say you don't get to fire a good worker based on sex or gender non conformity. That's sex discrimination.

In both cases, the employer came back and said, 'yes we're a for profit business, we're not a religious organization, but I the owner or we the owners have these strong religious beliefs and we are exercising our religion in the way we run our business. We have these religious beliefs about how other people should behave, and we believe that if we don’t object, if we have any connection to what someone else is doing, then we're endorsing what they're doing and showing our support for what they're doing. And if we believe what they're doing is sinful or against God's word, then we think we are sinning as well.' In Hobby Lobby the court accepted that idea and in this case the court is accepting that idea.

The way that the court got to that conclusion was by applying the test that's in this Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Congress wrote this law, passed it in 1993, which sets out a three part test, and then life percolated along in a somewhat unsurprising way until we got to Hobby Lobby.

In Hobby Lobby, the Supreme Court reinterpreted how that test is supposed to be applied in ways that opened the doors to a case like this.

ATTN: How was the test interpreted?

JP: The test asks first whether the employers have a sincere religious belief and if their ability to exercise their faith substantially burdened.

So in this decision, the court — in my view — misapplies that element of the test by taking the word of the defendant that they feel burdened. The decision acknowledges that this is supposed to be a legal question but then doesn't evaluate it from an objective point of view. So it just kind of collapses that element of the test into 'do you sincerely believe that your belief is burdened, and if so, ok, then you get to sue.' That's not what the test is supposed to mean. The word substantial is supposed to mean something.

Then we get to the next element of the test: does the government have a compelling interest in enforcing the nondiscrimination law?

Well, we have case after case over the years where the courts have said society has a compelling interest in ending discrimination. Ending discrimination has been one of the most important goals of our evolving society. As we've grappled with being a diverse and pluralistic society, those non discrimination laws have been absolutely essential for our society's ability to move forward.

So in this instance, the court has this peculiar way of inquiring about that element and concludes it must not be a compelling interest because the EEOC is not seeking to abolish the gender differentiated dresscode.

The question is, is this individual worker being fired — losing her job — based on her nonconformity with someone else's ideas about what a man or woman is supposed to be? The court kind of got that question backwards to a certain extent.

Then, the third element of the test is whether there is some less restrictive means for pursuing the compelling interest. The court offers some discussion of 'well, EEOC did not explore with the funeral parlor if it would acceptable to both parties if transgender woman was free to dress in female attire when she's not at work and with a suit and tie at work.'

So the court completely misunderstands what the needs of a transgender person are. The least restrictive alternative test is supposed to mean the way that you eliminate discrimination without reaching too broadly and interfering with a range of other needs or interests. It's not that the court is supposed to insist on reducing the discrimination but allowing some kind of compromise that the employer would like better.

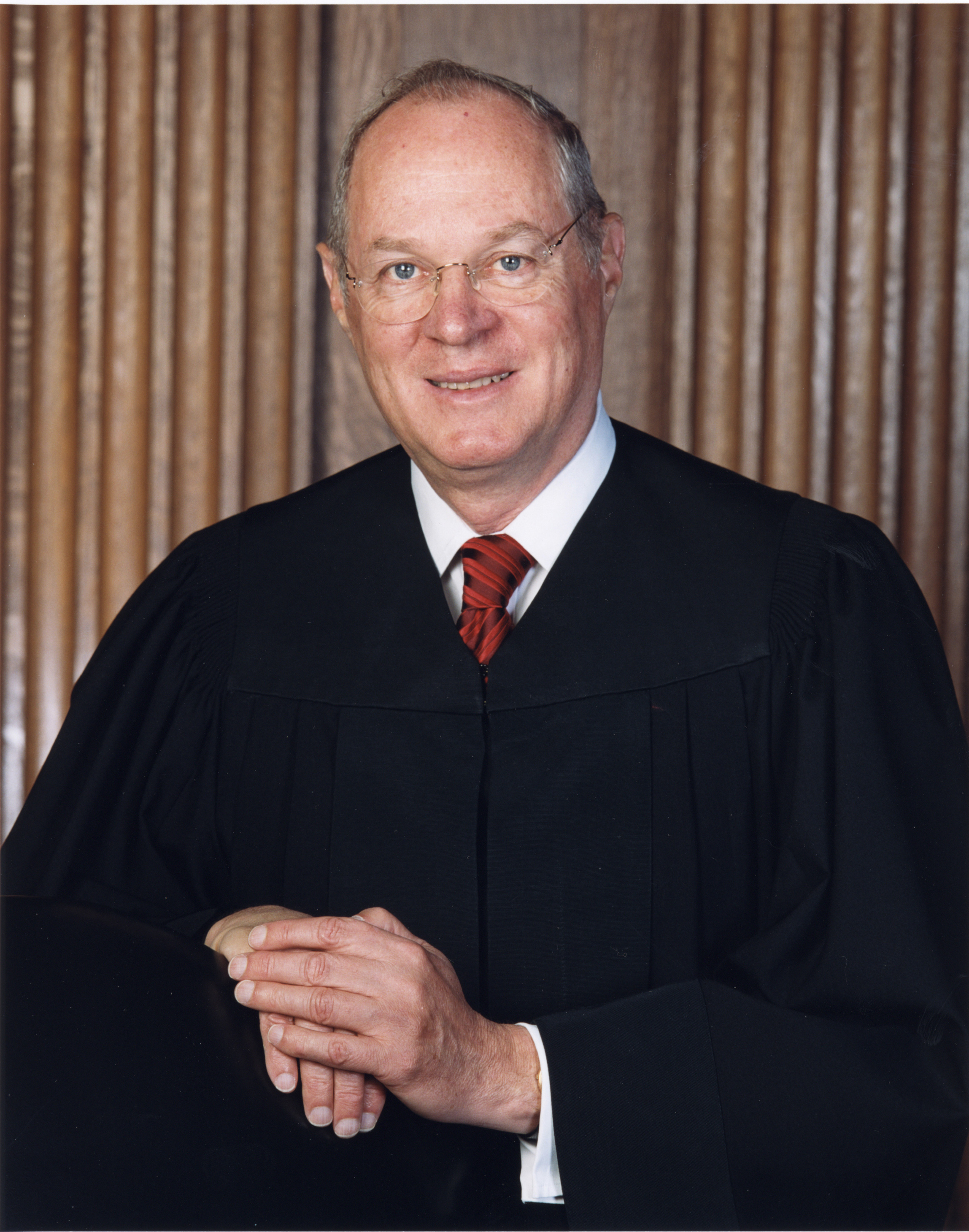

Another confusing and problematic part of the decision is that the judge draws from ideas from the Hobby Lobby majority opinion and some ideas from the dissent but actually misses the core idea that was in a concurring opinion that Justice Kennedy wrote. And he was the only justice that joined it. Without his concurring opinion, the majority would not have been a majority. So his idea is essential to Hobby Lobby having won.

Wikimedia Commons - wikipedia.org

Wikimedia Commons - wikipedia.org

That idea [from Kennedy] was we want to accommodate religious beliefs and practices as much as we can but not when they would permit discrimination or would sacrifice the needs of employees because they have their own compelling interests.

We have religious freedom up to the point that somebody else would be harmed. It shouldn't really be a question in anybody's mind that being fired because your boss has an idea that God considers the two genders to be different and immutable — that’s a protected religious belief, but if an employer fires people based on nonconformity with that religious belief that's harmful to the person who lost their job.

ATTN: Have you seen cases like this in terms of anti-LGBT discrimination?

JP: [They’re] starting to come forward.

If we're talking about anti-LGBT discrimination, there needs to be protection for the LGBT person in the first instance in order for that person to have a legal right to complain if they are discriminated against.

We've seen a bunch a different cases under state law where either the state version of this kind of religious freedom law or a state constitution is invoked. We have seen it much less at the federal level because it's a relatively new development that the courts and the EEOC and the federal agencies are recognizing that the sex discrimination protection that we already have at the federal level does protect LGBT people because the discrimination against us — most of the time, if not all the time — is about conformity with stereotypes.

There’s a similar reasoning about gender identity. People have their ideas about what a man is, what a woman is, how you behave, and that these characteristics don't change. So it’s relatively recent that the federal courts and federal agencies have come to recognize that this anti-LGBT discrimination is a form of sex discrimination.

So, this is just another form of sex discrimination, but the law is developing now and as there's more recognition that federal law offers protection, then you see these cases happening.

And you certainly weren’t going to see this kind of argument before Hobby Lobby, because the courts did not read the Religious Freedom Restoration Act this way. The Hobby Lobby decision was truly a radical re-interpretation of what that statute means, and that interpretation opened the door for what we think is profoundly misunderstanding or misapplication of that federal law.