Grade Inflation Is out of Control in the U.S.

By:

If you're the kind of student who measures success in letters on a transcript — and let's be honest, the competitiveness of higher education often demands it — now is a good time to be in school. It's much easier to land A's in your classes, no matter where or what you study in the U.S., compared to past decades, a new study from GradeInflation.com found.

The Washington Post - washingtonpost.com

The Washington Post - washingtonpost.com

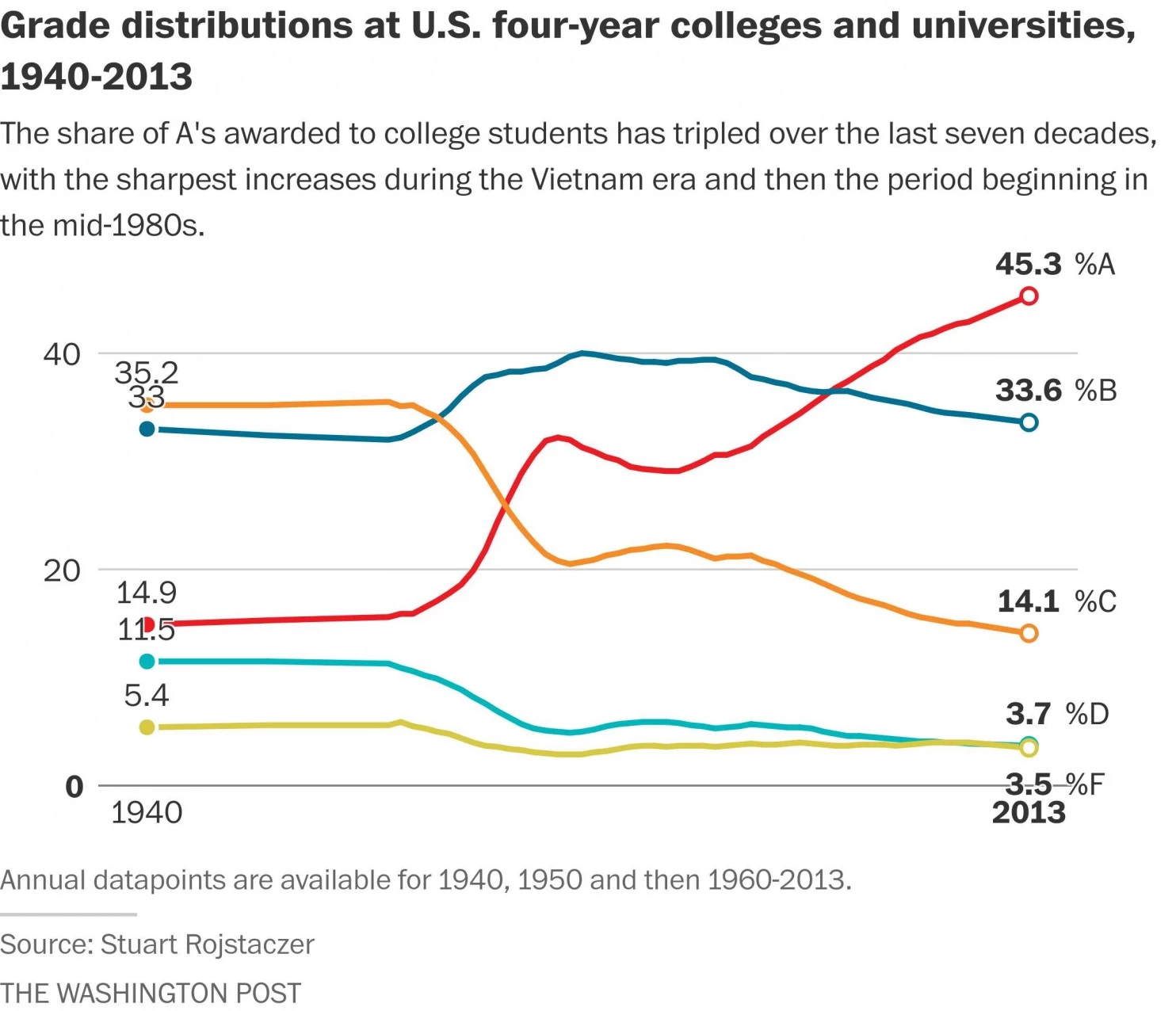

The distribution of grades has shifted dramatically since the 1940s, when A's only accounted for 15 percent of college grades. Now the portion of top academic marks is triple that amount, accounting for about 45 percent of total grades. This evidence of grade inflation came after researchers looked at transcript records from 400 public and private schools.

It doesn't matter if it's an Ivy League school or community college, nor does it matter what kind of class the student takes, The Washington Post reports. The trend holds true across all subjects and institutions, raising questions about the function of higher education in the U.S. today and the impact of grade inflation on students' ability to compete in the workplace after graduation.

"There are a small number of schools (about 15 percent of all schools in our database) that have experienced only modest increases in GPAs over the last 15 to 20 years, but most of them have average GPAs that already exceed 3.0," researcher Stuart Rojstaczer wrote. "There are no schools in our dataset that have been untouched by rising grades over the last 50 years."

Why are grades on the rise in American colleges?

There are a couple theories as to why students are receiving higher marks even though academic performance has remained generally consistent through the mid-1900s. One of the most compelling arguments is that there's a greater expectation for a return on educational investment as the cost of a college education has increased — a trend that Rojstaczer describes as the "consumerization of higher education."

If students are going to leave college with over $29,000 in student debt on average, there tends to be an increased demand for better facilities, services, and even grades. Part of the tradeoff for rising tuition, it seems, is higher grades, which would hypothetically allow students to boost their employment or graduate school admission prospects.

"And indeed, some universities have explicitly lifted their grading curves (sometimes retroactively) to make graduates more competitive in the job market, leading to a sort of grade inflation arms race," The Post reports. "But rising tuition may not be the sole driver of students’ expectations for better grades, given that high school grades have also risen in recent decades."

Another theory concerns the role of professors in grade inflation. Rather than an active move by administrators, it's possible that professors are responsible for gradually inflating grades in an effort to elicit better teaching evaluations, for example. Evidence of that pattern is hard to come by, however.

"It’s unclear how the clustering of grades near the top is affecting student effort," The Post adds. "But it certainly makes it harder to accurately measure how much students have learned. It also makes it more challenging for grad schools and employers to sort the superstars from the also-rans (which, if you’re an elite school like Harvard, is probably a feature, not a bug)."