The Bizarre Way True Crime TV Is Shaping Jury Selection

By:

True crime makes jurors of us all. Programs like "Serial," "The Jinx," and "Making a Murderer," tell provocative, personal stories, giving viewers privileged glimpses into a criminal justice system that is often faceless and difficult to comprehend. But researchers and trial consultants worry that these programs, along with fictional shows like "Law & Order," may transmit undue biases onto future juries.

Flickr/Cfiesler - flickr.com

Flickr/Cfiesler - flickr.com

"The new wave of true-crime narrative feels tantalizingly two-way, as if it were a virtual invitation from filmmakers and producers to help demystify the criminal-justice system." Kenny Herzog writes on Vulture. "But does that suggest that, post–Steven Avery, Brendan Dassey, Robert Durst, and Adnan Masud Syed — the aforementioned broadcasts’ polarizing subjects — attorneys will suddenly be selecting from a more cynical jury pool?"

The "CSI Effect."

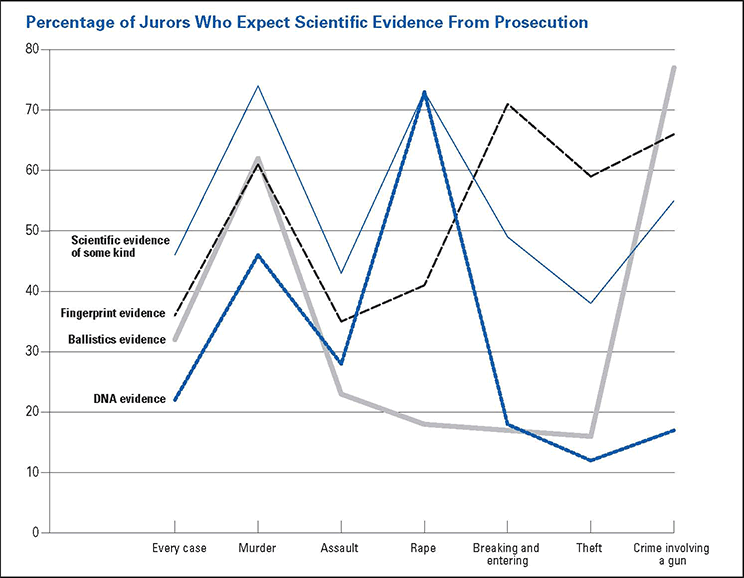

The idea that popular media might bias jury pools was first observed during the rise of the "CSI" and "Law & Order" television franchises. Termed the "CSI Effect," experts noticed that television crime dramas made jurors more focused on forensic science, and often found that the shows gave them unrealistic expectations about the forensic evidence required to convict people of actual crimes.

"The most obvious symptom of the CSI effect is that jurors think they have a thorough understanding of science they have seen presented on television, when they do not." The Economist reports.

NIJ - nij.gov

NIJ - nij.gov

"I once heard a juror complain that the prosecution had not done a thorough job because 'they didn't even dust the lawn for fingerprints.'" Donald Shelton, felony trial judge, wrote in a paper published in the NIJ Journal.

Pathologists like John Grossman, the undersecretary of forensic science and technology for Massachusetts, have expressed concern that jurors aren't aware of the gulf between crime fiction and real trials, where high-level scientific evidence isn't always available or pertinent.

"I think it makes it much harder for the experts," Grossman told NPR. "Juries now expect high-level science to be done on lots of cases where again we don't have the resources to do them and in many cases, the science doesn't exist to do them."

It's easy to simulate cutting-edge forensic science on television, but the reality is that many areas of the country lack the funding to do the kind of detailed autopsies or forensic investigations that take place on shows like "CSI" and "Law and Order."

Judge Shelton is skeptical of the impact of the "CSI Effect" on actual verdicts, but says the myth has made death investigators often run needless tests to align court proceedings with the unrealistic expectations of jurors.

"They will perform scientific tests and present evidence of that to the jury." Shelton told NPR. "Even if the results don't show guilt or innocence either way, just to show the jury that they did it."

How true crime impacts trial verdicts.

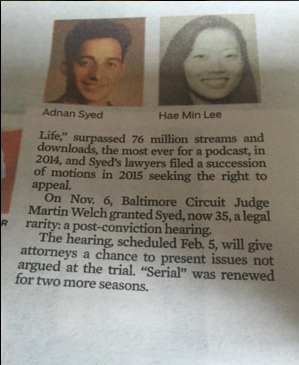

Though some experts are skeptical about the "CSI Effect's" actual impact on trial verdicts, both "Serial" and "Making A Murderer" have had real-life impacts on trial proceedings. Syed was granted a hearing after his case became a pop cultural phenomenon, and 160,000 people signed petitions to free Steven Avery after the release of "Making a Murderer".

Twitter/BobbyAllyn - twitter.com

Twitter/BobbyAllyn - twitter.com

Unlike the "CSI Effect," which instills specific, potentially faulty expectations about forensic evidence, the popular true crime docu-series of today may transmit a vague distrust of the legal system in their viewers.

Looking to get out of jury duty? Trial consultant Jo-Ellan Dimitrius, who helped select juries including Simpson's, believes that future jury selection may even involve questions about specific true crime programs and fandom.

“You would want to have the attorney ask: ‘How long did you watch [Making a Murderer]? With whom might you have had conversations about what you saw? Have you done anything in furtherance of your feelings about the show? For instance, some sort of social-media post,’” She told Vulture, adding, “We used to ask those questions about CSI because it was pretty predictive of someone who was a defense-prone juror.”

How true crime became popular again.

True crime wasn't always a part of mainstream pop culture. Quartz's Jake Flanagin cites a 2013 Atlantic cover story “Murder by Craigslist” as central in re-introducing the once-niche genre into the American mainstream, humanizing a murder case by exploring its socioeconomic context.

Twitter/lexpress - twitter.com

Twitter/lexpress - twitter.com

In a piece about the Atlantic's 2013 cover story, The New Yorker's Sarah Stillman wrote: "Rosin’s reporting began with a case that seemed destined to become mere tabloid fodder — the serial killings of men who answered online ads for a non-existent Ohio farmhand job." Yet, Stillman observed that the story "delivered the reader something else entirely: the piece used the brutal murders as a chance to examine the increasingly precarious lives of working-class men whose economic safety nets have been snipped out from under them."

The "This American Life" spin-off "Serial" arrived the following year. The podcast investigated the murder trial of Adnan Syed and was answered by countless think pieces and podcasts dissecting the murder of Hae Min Lee as well as the reporting of host Sarah Koenig.

The popularity of "Serial" is at least partly due to Koenig's narration and skill as a storyteller, inviting listeners into her quest for truth and discussing her investigative process openly.

“As she’s discovering new things, the listeners are discovering new things,” one fan of the podcast told The Washington Post. (Koenig recently spoke to The New Yorker's editor in chief David Remnick about "Serial" and the true crime genre in a fascinating podcast.)

Following "Serial," HBO's "The Jinx" and Netflix's "Making A Murderer" offered fans a similar experience, inviting them into provocative human stories about criminal investigations and the contexts in which justice or injustice is ultimately served.

Twitter/hypebeast - twitter.com

Twitter/hypebeast - twitter.com

Though the true crime trend has recently taken pop culture by storm, it isn't the first time the sleuthing craze has hit. Works like Truman Capote's "In Cold Blood" (1966) and Vincent Bugliosi’s bestseller "Helter Skelter" (1974), which chronicled the Manson murders, were both widespread cultural sensations that brought detective narratives about real people and events into the popular imagination.

Flanagin from Quartz believes the true crime genre is experiencing a resurgence because of increased awareness of social issues and the failures of the criminal justice system.

"A cultural obsession with glitzy, sensationalized cases—the murder of JonBenét Ramsey and the O.J. Simpson trial, for example—defined the genre in the 1980s and ’90s. This newest crop of true-crime entertainment is taking a different tack. Instead of fetishizing the criminal and the crime, Serial and Making a Murderer take a long, hard look at the contexts in which such atrocities arise, how we as a society deal with them, and whether our methods of delivering justice are as sound as they are purported to be."

What fascinates viewers of "Serial" is quite different than those who closely followed the O.J. Simpson trial. In particular, today's true crime fans are interested in the ways law enforcement and the criminal justice system fail marginalized individuals and those on the perceived outskirts of society.