Inside the Obsessive-Compulsive Brain

By:

In January 2010, Fiorella (who asked that we only use her first name) was 18 and a student living with roommates in Toronto. She was working several part-time jobs on top of pursuing an undergraduate degree in psychology. She was stressed out and overworked, but otherwise healthy.

By February, Fiorella could barely sleep and couldn’t eat. Getting dressed and leaving the apartment became a challenge. “I remember dreading going to the bathroom from my bedroom because it took so much time,” she says. “I’d get up, sit back down, get up, sit back down.” At night, she’d get into bed and then spring back up again, lie down and get back up, lie down and get up, maybe for hours. Or she’d pour herself a bowl of cereal, lift the spoon to her mouth, and freeze. “I’d bring the spoon my mouth, put it back down, bring it up and put it back down," she explained.* "It was very distressing to have to repeat everything and not know why."

And then there were the thoughts. Fiorella didn’t want to describe them in detail, but she says they were violent, graphic, and constant. They came out of thin air, it seemed, as if some malicious force had planted them in her head and pressed “play” over and over. Sometimes, repeating gestures and movements would relieve the anxiety she felt when these thoughts pounded at her. Mostly they didn’t.

“I didn’t know it was obsessive-compulsive disorder," she says. "I thought I was having a breakdown.”

After about a month she went to the hospital, where a psychiatrist promptly diagnosed her with severe OCD.

What is OCD?

Colloquially, “OCD” has come to signify someone who likes things just so. "You’re so OCD," friends have told me. I can’t leave a dish unwashed or my bed unmade; magazines need to be arranged in nice stacks, with sharp corners, and kitchen chairs must always be tucked under the table when not in use. Clothing must be neatly folded into drawers before bed.

OCD is fairly common, says Dr. Chris Pittinger, director of the Yale OCD Research Clinic and an associate professor of psychiatry, psychology, and in the Child Study Center at Yale University School of Medicine. It affects roughly 1 in 40 people. But the clinical definition is more complex than simply being a neat freak.

The disorder consists of two distinct but related symptoms, Dr. Pittinger explains, obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions, he says, “are intrusive thoughts that seem to come out of nowhere that cause anxiety and keep coming back again and again. Most people experience obsessive thoughts as being somehow different from their ordinary thoughts—more intrusive, more rigid, and they cause anxiety or discomfort." These thoughts are often frightening or disturbing. They often involve violent, religious, or sexual imagery. They can manifest as fears or worries, as vivid tableaux, or even as an urge to do something terrible. The key is that these thoughts or urges are “intrusive and foreign” and produce significant distress, Dr. Pittinger explained to ATTN:.

Compulsions are the routines or rituals that emerge as a result of these thoughts. "They're the behaviors that people do in order to try to alleviate the anxiety or discomfort,” Dr. Pittinger says. “The compulsions work only incompletely or intermittently [to relieve the anxiety], so people tend to engage in them more and more to try to get the relief they’re seeking.”

Combined, the obsessions and compulsions can take a fairly reasonable thought and transform it into a prolonged terror. For example, "you might have a fear that if you don’t lock the back door, someone may come into your house and kill your kids. Having that thought isn’t necessarily unreasonable. And then going and checking the back door [to make sure it’s locked] is perfectly reasonable. But having that thought come back again and again, so that you lie awake for three hours and check the door 50 times without being reassured, is excessive," Dr. Pittinger says.

The obsessions and compulsions can also be rooted in superstition—“things along the lines of ‘step on a crack and break your mother’s back,’" he says. "I’ve had patients who felt something dreadful would happen to a soldier in Afghanistan if they didn’t do X, for example.”

The disorder believed to involve both genetic and environmental factors. It seems to run in some families, but typically there must also be some sort of developmental or environmental trigger, such as a neurological or psychological trauma or a period of intense stress. “We talk about ‘gene-body interactions,’” says Dr. Eric Hollander, director of the Autism and Obsessive Compulsive Spectrum Program and the Anxiety and Depression Program, and a clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in New York. “There are some people who are more likely to have the onset of the illness if they have these environmental factors and certain genetic vulnerability.” (There's also a subset of children who seem to develop OCD after an infection, suggesting that it can be triggered by an autoimmune response, but this remains a somewhat controversial proposition for OCD researchers.)

Hyperactive brain circuits.

Fiorella recalls how her obsessive thoughts felt incessant and foreign. “I felt like I couldn’t shut my brain off," she says. "I was constantly being bombarded with these upsetting thoughts and images—like my brain was constantly ‘on.'"

People with OCD often describe their minds as being overactive, impossible to shut off. Brain imaging studies suggest they're not entirely wrong.

There's a lot left to learn about the causes of OCD, but at least at the level of brain activity, researchers think they have a pretty good idea of what’s happening in the obsessive-compulsive brain. “There are particular regions in the brain that are hyperactive in people with OCD, and they get even more over-active when the symptoms get bad," Dr. Pittinger says.

aboutmodafinil.com - flickr.com

aboutmodafinil.com - flickr.com

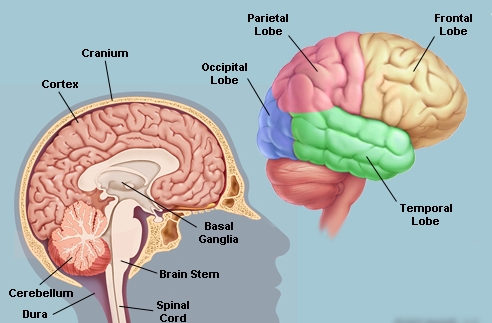

OCD appears to stem from hyperactivity in certain brain circuits, which transfer information from one region to another and back again. The exterior layer of the brain, called the cortex, transmits information to the basal ganglia, a set of structures located beneath the cortex. The basal ganglia process that information and send it back to the cortex. “It’s a loop," Dr. Pittinger explains. "And in people with OCD, certain parts of the cortex—especially subsets of the cortex in the front of the brain, which process more abstract ideas—are hyperactive, as are several structures within the basal ganglia.” That hyperactivity makes the circuit less able to filter out unnecessary information.

There are a number of parallel circuits that kick into overdrive in OCD. Two may be of particular significance, Dr. Pittinger says. "One is between the orbitofrontal cortex, which is involved in emotional regulation and behavioral flexibility, and a part of the basal ganglia that's involved in motivation and reward—the processes that drive us to do things." The second is between a part of the frontal cortex and the putamen, "known to be involved in habit learning—when things you've done a thousand times become automatic. In the process of becoming automatic, they also become inflexible."

Over time, these hyperactive circuits "become more and more ingrained, more and more automatic,” says Dr. Hollander. The result is that the obsessions and compulsions can become more severe over time, and harder to treat.

A variable disorder.

Not all cases of OCD are crippling. Samantha Escobar, a 25-year-old beauty editor in New York, was diagnosed with OCD at 16, but she'd been fixated on numbers and balance even in childhood. “I’d cut all my food into an even number of pieces so that I could chew one bite on each side of my mouth," she says. "Otherwise I felt very unbalanced." She also began tapping her fingers, a common tic among people with OCD. She developed a specific rhythm for the tapping so that "the tapping fingers aren’t adjacent to one another, and I have to do it in different patterns, back and forth."

At work, she says, "I sometimes feel I have to go back and delete things and rewrite them. If I misspell a word, I have to then spell it a couple times properly.” (She compensated for this by becoming an extremely fast typist.)

When Escobar was first diagnosed with OCD, a psychiatrist prescribed medication, but she rarely took it; she was already taking meds to treat anxiety and depression, and had been reluctant enough to take those. (Anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric issues are common in people with OCD.) She eventually stopped taking medication altogether.

Over the years, Escobar says, she's picked up new compulsions and lost others; she no longer pulls out her hair or picks at her skin, for instance, but she's started grinding her teeth. These tics are subtle and mostly manageable, but they're not going away. When she meets new people, she becomes self-conscious and spends most of her energy trying to subdue them. “I regularly wonder what other people’s lives are like without OCD," she says. "I can’t imagine how amazing it must be to be able to concentrate on things without having something else you’re concentrating on all the time.”

Treatment options.

For those who do pursue treatment, the American Psychiatric Association recommends a certain class of antidepressants—selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs, which include Prozac, Paxil, Zoloft, Celexa, and Lexapro—and cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT. Both have been shown in clinical practice and on brain imaging studies to calm the circuits that become overactive in OCD.

SSRIs appear to suppress the hyperactive brain circuitry by modulating the amount of serotonin that flows through the over-active circuit, while CBT attempts to retrain the brain and loosen the grip of these hard-wired repetitive behaviors, Dr. Hollander explains. Often, CBT for OCD involves a form of exposure therapy: getting the patient to tolerate the discomfort of an obsessive thought without performing the associated compulsion. “The discomfort ultimately goes away on its own,” Dr. Pittinger says. “That may happen quickly, or it may take a while, but ultimately you realize you don’t need to engage in a compulsion in order to feel better. And as you spend less time engaged in the compulsions, you take the fuel off the fire. You've reduced this feedback loop [in the brain].”

Outcomes for patients who receive treatment are variable. “Some people will go into remission and stay in remission indefinitely," Dr. Pittinger says. "Some people will go into remission but may have other episodes later in life. It’s probably most common for people to have symptoms retreat, but not vanish, and they learn skills to manage the symptoms so they don’t affect their lives as much. And some people, unfortunately, don’t respond."

Now 24, Fiorella takes a combination of antidepressants and antipsychotic medication, sees a therapist, and has participated in CBT. She's working several jobs again, including as an adult literacy tutor and as a circulation manager for a Toronto-based magazine. Her compulsions have faded to just a few subtle tics, she says—a tilt of the head now and then, or the occasional incident where she'll take a carton of orange juice out of the fridge and feel the need to put it back in before taking it out again. “There will be days where I don’t engage with the compulsions at all,” she says.

Therapy has helped Fiorella understand and even accept the graphic thoughts that caused her so much pain. “I thought, does this mean I’m a bad person?" she says, when they first began to pop into her head. "It was so liberating to hear my psychiatrist say, ‘You are not your thoughts. You actually have very little control over your thoughts, and they’re not a useful measure [of who you are].’”

OCD “is something I still deal with every single day, but I manage it now,” she says. “I mean, there’s still part of me that wishes things will magically fix themselves and I won’t need medication anymore. But I don’t think that’s in my future. I think this is something I’ll have to live with forever, and I have, to some degree, made peace with that.”

*A previous sentence about trichotillomania has been removed. Fiorella never had trichotillomania.