Why We Need to Change the Way We Design Prisons

By:

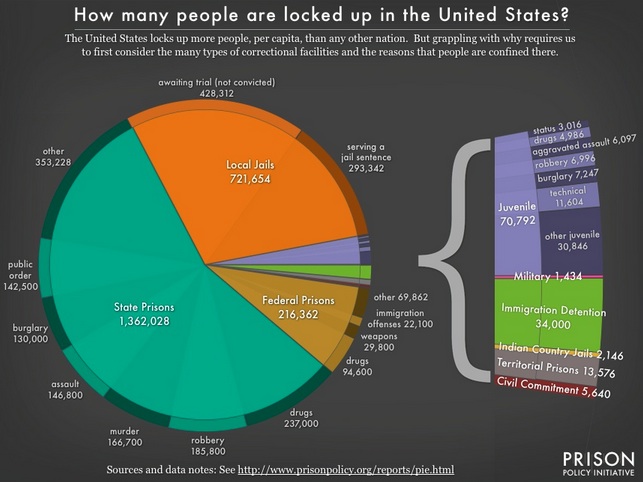

More than 2.4 million people in the U.S. live behind bars, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. Since the 1960s the prison population in the U.S. has risen steadily, even during periods where the crime rate has dropped. Due to reports of abuse in the past several years, there has been an increasing pressure to reform the prison system and redesign how America incarcerates inmates.

Prison Policy Initiative - prisonpolicy.org

Prison Policy Initiative - prisonpolicy.org

An architect goes about designing a prison the way they go about designing most other spaces: by looking at the mission of the building. In the case of prisons, the answer is not so clear. During the 1800s, prisons were used only for the purpose of punishing and detaining criminals. But recently, policy makers and advocates have pushed for prison reform. They argue that mere punishment and deterrence is not sufficient because more than half of prisoners who finish their sentences and are released back into society will commit crimes again. These policy makers and advocates are pushing for more rehabilitative prisons, which would mean more humane conditions for the prisoners.

Prison design has reflected this shift in thinking. In the 1800s, jail spaces were divided into cage-like dayrooms and prisoners had little contact with the staff. In the 1960s, jail design changed to a linear fashion, with cells built along long corridors in a hospital-like fashion. These cells were under surveillance by video cameras but prisoners still had little contact with staff. Both these prison models have been criticized for unsanitary conditions and overcrowding. By the late 1970s the U.S. Bureau of Prisons and the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, U.S. Department of Justice and several leading architectural firms led an effort to create a more humane prison design. They came up with the currently favored design: the pod structure. Pods are single-occupancy rooms that surround a day room. Detention officers are stationed in an open work area at all times to maximize inmate-staff interaction which reformists argue will encourage more positive relations between detention officers and inmates.

In addition, an increasing number of prisons are also incorporating mental health facilities in their prisons. For example, the U.S. penitentiary in Atlanta recently opened the first federal prison program to provide substantial long-term care and treatment for high-security mentally ill inmates.

Balancing safety and quality of life is tricky business says Lorenzo Lopez, Chair of the Academy of Architecture for Justice. Prison design is often restricted by a mind-boggling amount of building codes and strict budgets. Prisons have to be fireproof, have sprinklers and must be divided many fire and smoke-tight compartments and corridors. New building designs need to meet Prison Rape Elimination Act requirements, which eliminate blind spots and maximize views into prison areas. Designers also have to build as many barriers between the officers and prisoners as possible. On top of all this, architects have to find some way to provide adequate medical, mental health, dental, disabled accessible amenities, and religious services. This does not allow architects much leeway in terms of design.

“The design of prisons is more about being creative with the building plan in order to maximize operational efficiency, sightliness, and security while allowing for the safe movement of occupants and materials,” said Lopez.

Some architects are taking a stand against designing prisons. Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility founder Raphael Sperry argues that architects are complicit in the inhumanity of prisons such as the Pelican Bay State Prison – a 275-acre super-maximum security facility criticized for its solitary confinement cells. Sperry launched a petition last fall urging the American Institute of Architects to update its code of ethics to ban architects from designing spaces for killing and torture.

On the other hand, architects elsewhere in the world have shown that they can be a force for prison reform. In Norway and Australia, designers have experimented with much more humane types of prison design: convicted murders and rapists have access to woodland jogging trails and climbing walls and the landscape is fully integrated into the design. Norway has only a 20 percent recidivism rate compared to U.S.’s 43 percent.

Correction: This post was updated on June 29 to include the correct number of inmates in the U.S.