How You Should Talk About Mental Health

By:

Mental health is a topic that invokes a great deal of public anxiety. People generally don't like to talk about it, except through common often pejorative phrases -- "I know this will sound crazy," "stop being such a psycho!" Research has also shown that negative attitudes toward mental health issues start early and persist throughout life. In one case, a long term follow-up study demonstrated that young adults displayed the same prejudicial beliefs about mental health challenges as they had eight years earlier.

Even worse, it appears that some of us may be acting on our prejudices. A recent survey in California reported that nine in 10 respondents who acknowledged a mental health problem also experienced discrimination based on it. In the same study, Californians indicated that less than half of people were "generally caring and sympathetic to people with mental illness." What can be done?

I don't believe that most of us are ill-intentioned, and I was shocked to discover how un-supportive my fellow Golden State residents were perceived to be. After all, mental health issues are pervasive. Almost 50 percent of US adults will develop at least one form of mental illness at some point in their lifetime, according to the CDC, and the National Alliance on Mental Illness states that one in four American adults have a mental health issue at any given time. If mental health difficulties are so widespread, why are they so hard to talk about? One word: stigma.

Why is stigma so powerful?

Stigma against those with mental health issues is real, and it prevents many from getting the help they may need. Four out of five people believe that it's harder to admit to having a mental illness than any other illness. This statistic is sadly unsurprising. A survey done in the United Kingdom showed that while 62 percent of employers would considering hiring someone with a physical condition, only 40 percent would hire someone with a mental health condition.

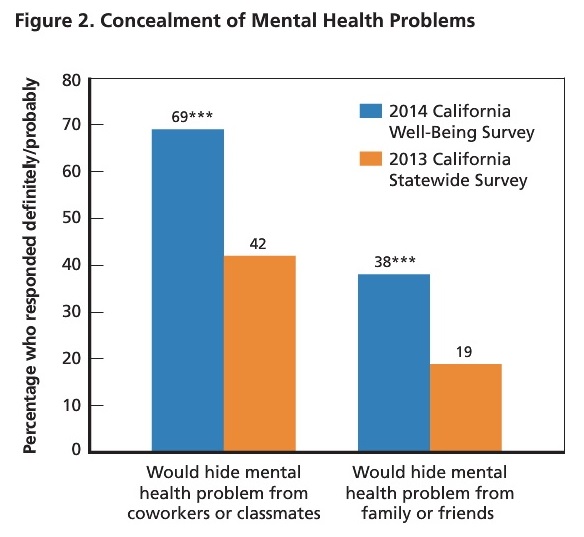

This level of casual discrimination underpins two key facts that show the damage of stigma. Less than 40 percent of those struggling with their mental health seek help and almost the same number would hide their mental health problems from their friends or family. (An even higher percentage would hide mental health issues from a classmate or colleague.)

What if we were talking about breast cancer? Or diabetes? Both of these conditions are less common than mental health issues, and yet popular wisdom would never be to avoid medical treatment or "just feel better" -- a phrase frequently heard by those suffering from depression.

Despite being a largely invisible problem, mental health is no less serious and no less potentially deadly. Sadly stigma stops individuals from being open about mental health -- individuals like Robin Williams, who committed suicide last year. "Robin Williams didn't kill himself, stigma killed him," an anonymous online mental health advocate powerfully noted. "It kills many people like him everyday."

So how can each of us be better mental health allies? ATTN: talked to mental health professionals about ways to reduce both stigma and other barriers to this important conversation. Here's what we found.

1. Be a better mental health ally by truly listening.

"I think that you always have to ask the person their experience and what they want," said Rabbi Rachel Bat-Or about the power of listening. Bat-Or is marriage and family therapist (MFT).

Experiences of mental health issues are often devalued or lumped together, so a good ally will take the lead of the person who is struggling, listen to their experience and try to understand what it is like for that particular individual without making assumptions. However, allies need to be thoughtful, as questions are not always helpful or appropriate.

"You can't ask intrusive questions," Bat-Or explains. "You have to be curious for their sake and not for your own sake. 'How do you experience this?' However they define it. 'How does that work in your life?' And then to say, 'What do you need? How can I support you?'"

To emphasize this point, Bat-Or told me a story about a blind woman who came up to her in the supermarket and asked Bat-Or to tell her where the entrance was. In an effort to help, Bat-Or took the stranger's arm and said she'd lead her there. The blind woman strongly pushed her off, stating that she had asked her to tell her not show her and walked away. After her initial surprise, Bat-Or realized that the interaction had probably come off as patronizing. "It wasn't the kind of help she needed, and I hadn't listened carefully," Bat-Or explained. "It's really important for us to listen carefully to what people need. The balance is what is helpful and what is intrusive."

This is similar to when friends try to support my gender transition by asking intrusive and inappropriate questions about surgeries and my genitals. It is important to think about why you're asking a question -- is it prurient or helpful? -- and then listen carefully to the answer, letting the other person disclose as much or as little as they are comfortable with. Breaking down these stigma barriers is difficult work on both sides.

2. Be a better mental health ally by educating yourself and speaking up.

One of therapist Jessica Bernal's top priorities is public education.

"Education helps us learn about what these things look like and to understand that there are people all over every day that are super high-functioning -- that have an education, jobs, partners -- and have mental health issues," Bernal, a licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT), told ATTN:. "I don't use the word 'normal,' but I use the word 'normalizing.' [Education teaches people that] what it looks like is not what [they] thought it would look like."

Common language around mental health problems skews towards negative imagery -- psychokillers, maniacs, and descriptors like nuts and crazy. According to one report, even psychiatry and psychology professionals aren't immune to stigmatizing their patients by making negative value judgments following a diagnosis. It's extremely important that we engage in some myth-busting ourselves and take responsibility for the language we use to talk about mental health in our daily lives.

To articulate the problems that exist around mental health and language, Bernal connects it with the phrase "that's so gay," which is no longer socially acceptable.

"You may be in the break room at work, and someone says, 'Something something that's so gay.' It use to be socially acceptable to say that, and it was turned into something where it was not acceptable," notes Bernal. "By the same token, the same should be the case when someone say that their boss is ... crazy and so bipolar. You don't know who is in the room."

In fact, with the prevalence of depression and other common mental health challenges, the chance that someone in the room is personally affected by mental health struggles -- either their own or a close friend or family member's -- is quite high. Knowing the real face of mental health by educating yourself, being conscious of the words you use, and speaking up when someone else says something hurtful will put you on the path to being a better ally.

3. Be a better mental health ally by taking care of your own mental health and encouraging others to do the same.

J.K. Rowling is more than a great author; she's also a strong ally for those that have struggled with their mental health -- including herself.

"I have never been remotely ashamed of having been depressed," Rowling told a student journalist. "Never. What's to be ashamed of? I went through a really rough time and I am quite proud that I got out of that."

Other celebrities have also spoken about their own mental health difficulties, changing the public dialogue and encouraging people to overcome perceived stigma and get help.

While individuals may not have the same media impact, they can set a positive example for friends and family. If you see a friend or family member struggling, you can reach out and tell them what you've noticed. But 'therapizing' your friends is always a no-no, many of the mental health professionals explained.

"Don't try and be their therapist," cautions Bernal. "Just try and be with them and be a friend."

Remember that it's helpful to offer to listen and to encourage someone to seek assistance if they need it. However you are not a professional and also may do more harm than good by ignoring that fact.

A good tip to remember when engaging in these conversations? "Be understanding of the limitations of friends who are struggling without losing your own boundaries," MFT intern Erin Kilpatrick explained to ATTN:. "Respect the boundaries of the friend who is struggling without judgment or frustration."

Even therapists encounter challenges talking about these issues with friends.

"I think that therapy is a great resource for everyone," Bernal told ATTN:. But when she was talking to a friend who was going through a tough time and said, 'You should think about going to a therapist,' her friend balked. "She got really upset. I'm not going to perpetuate stigma ... but you still have to handle it delicately because of where we're at as a society."

4. Be a better mental health ally by advocating for better policies around mental health care.

On top of being more mindful of what you say, developing listening skills, and speaking more openly about the importance of mental health care, there's still more that can be done to be a better ally. It starts with pushing for better policies around mental health care. While President Obama has done more for mental health care than any other administration in the past 30 years, there's still progress to be made, starting with improved coverage for mental health services within insurance networks.

"More and more, health insurance and Medi-Cal are covering services like this," said Bernal of the improving situation. However, coverage often isn't enough. She pointed to health insurance giant Kaiser Permanente, which only covers therapy once per month for most of those insured under their plans. "Depending on what you're struggling with, people need therapy anywhere from once a week to three times a week or more. There's movement in the right direction, and once the health care system can get on board with providing adequate treatment that will start to erase stigma."

"People will see that there's nothing wrong with getting these services," Bernal continued.

Kilpatrick echoed Bernal's comments. "The system is so complicated and expensive," Kilpatrick said. "I think we need to lobby insurance companies and congress for better coverage. Once insurance companies (if they ever do) start treating mental illness holistically and seriously, like heart disease, it will change stigma."

To get more involved, check out organizations like the National Alliance on Mental Illness at www.nami.org. And since mental health is already a concern for the 2016 election, you can also do your part by staying informed about candidate positions on these issues.