How Children Chronicle War, From Bosnia to Syria

By:

"If it turns out to be another 'Lebanon,' as they keep saying, I'll be 30,” the girl wrote. “Gone will be my childhood. Gone my youth. Gone my life. And I'll die and this war still won't be over."

Flickr / legio09 - flickr.com

Flickr / legio09 - flickr.com

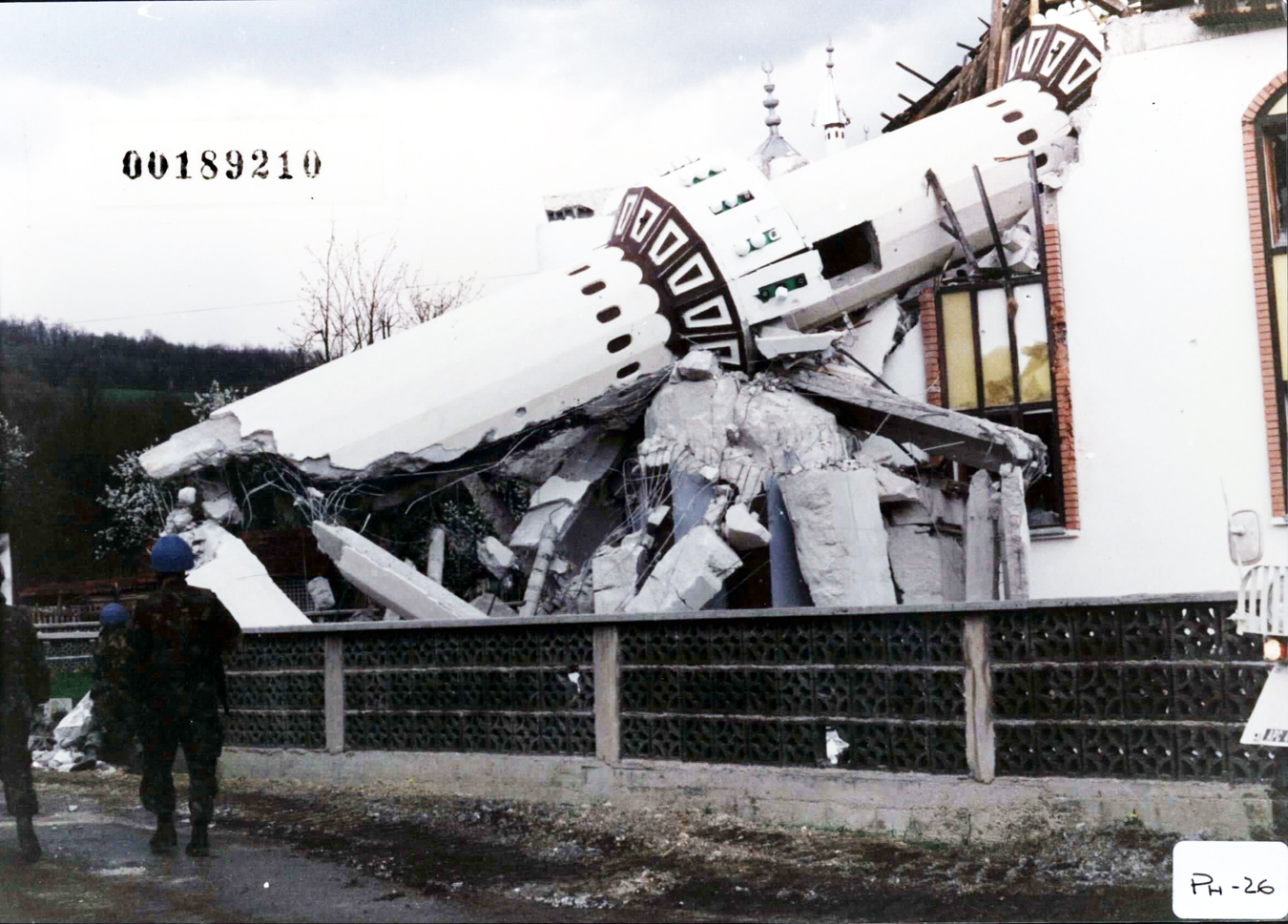

Zlata Filipovic was 11 years old when she began chronicling her life under siege. Serbian forces were firing over of 329 shells a day on the Bosnian city of Sarajevo, killing over 1,500 children and wounding 15,000 more. The media compared her diary, an international bestseller after it was released by a local publisher, to Anne Frank’s account of Nazi occupation — and the fame got Zlata and her family evacuated to Paris. There, she pressed for action to help the others who were left behind.

"When people read my book, when they see me on television, [I hope] they may help the children of Sarajevo,” she told The New York Times in 1994. “We must not forget the children."

Zlata, now 36 and a documentary film producer based in Dublin, Ireland, told ATTN: that, were she writing today, she might well have chosen to make her appeal for action using a medium more popular with today’s youth: websites like Twitter and Facebook. "Everything we now do does not exist if it has not been 'liked' and approved by others," she laments. "If a tree falls in the woods, but no one has put up a picture on Instragram, does it exist?"

She prefers the older, quieter approach to chronicling one's life, but "it's generational," she says. But because her private thoughts were eventually published and made public, she's familiar with the backlash that would take place on social media.

"When my diary was published, some people who did not believe the siege of Sarajevo was actually happening — and that it was all propaganda — did question of my diary," she tells ATTN:. "There was also some questioning of whether it was me who wrote it, as it portrayed a mature kid. But what they forgot is that childhoods are stolen by war and every kid becomes more mature — unfortunately."

If young Zlata were publishing her chronicles of war today, she would also be dealing with another reality of modern life and warfare: critics questioning her every claim, her motives, and even her existence in real time, and in 140 characters or less.

Bana Alabed, a 7-year-old Syrian, is testament to that.

In September, her mother, Fatemah, opened a Twitter account in Bana’s name, using it to share photos, videos, and her daughter’s thoughts from the besieged, rebel-held neighborhoods of eastern Aleppo.

“I am sick now, I have no medicine, no home, no clean water,” reads a tweet from December 1. “This will make me die even before a bomb kill me.”

The account personifies a situation that is typical of the “living nightmare” that is life for more than 100,000 children trapped in besieged eastern Aleppo, according to UNICEF. The city is being bombarded with the worst modern air power has to offer, with reports of dozens killed every day by cruise missiles and barrel bombs, their bodies left to decompose in streets from which it is too dangerous to remove them. The city is blocked off from the world, and the United Nations says food, clean water and medical supplies are in short supply, with a spokesperson describing the situation as a “slow-motion descent into hell.” In addition to regime attacks, eastern Aleppo is surrounded by opposition militants, from more moderate nationalists to international extremists, who have themselves committed war crimes like torture and indiscriminate attacks on neighborhoods in Aleppo's western half.

The reality is bleak and undeniable.

Civilians “are being bombed by Syrian and Russian forces,” in the words of the United Nations’ Secretary-General for humanitarian affairs, “and if they survive that, they will starve tomorrow.”

The internet is a way for those whose voices are being silenced to address the world — for the desperate to appeal to the world by way of a simple reminder that those suffering far away have hopes and fears and all the curses and blessings of the human condition, too. But there will always be skeptics, and on the internet there have always been trolls, and as journalist Amr Salahi noted for Pulse Media, the skeptical trolling has “come in various forms, ranging from crude death threats to accusations of forgery.”

“Your jihad days are over,” reads one tweet. “Now it’s payback time.”

The accusations of fraud, meanwhile, are necessarily left incomplete: it’s not clear, for instance, whether we are to believe Fatemah and her daughter simply do not exist, or that they do not live where they claim, or that they are legitimate but still playing the rest of us in a geopolitical game that’s way over our heads.

Some of the more historically literate may point to the infamous congressional testimony of a 15-year-old girl named Nayirah, who in 1990 falsely claimed to have seen Iraqi troops ripping babies out of incubators and leaving them to die. Operation Desert Storm, a U.S.-led effort to push Iraqi troops out of Kuwait, would begin months later. A year after that Nayirah was revealed to be the daughter of Kuwait’s ambassador to the U.S., working for a public relations campaign.

We know who Bana is and what she's going through.

As various United Nations officials can attest, there is nothing salacious about Bana Alabed's description of life in besieged eastern Aleppo. Her identity has been verified by Twitter and the BBC has interviewed her and her mother, but the reality of her existence and the existence of thousands of others like her has not moved any state or global institution to intervene on their behalf

The Syrian regime and its Russian allies know this, trumpeting their confidence in the status quo in a message to eastern Aleppo's residents.

“You know that everyone has given up on you,” read a leaflet recently dropped on Bana’s home city. “They left you alone to face your doom and nobody will give you any help.”

Still, while President-elect Donald Trump has at cooperation instead of confrontation with Syria, there are some who view a child in pain and see only dark manipulation into global conflict.

Why do skeptics raise doubts about Bana's account?

Some "skeptics" are mere partisans for those inflicting the most damage, both celebrating and denying it. Others may think they are preventing another unjust war, seeing through the lies of mainstream media — a posture that can turn bad when skepticism becomes reflexive denial of any unwelcome reality that sometimes makes the news.

It is reasonable to question stories emanating from a war-zone that is largely cut off from the world, but a healthy skepticism responds to new information, rather than posing rhertorical questions with no real desire to uncover an answer.

Take the question of Bana's internet access: How does one stay connected even as bombs are falling all around? That's meant to be a tough one, but it was quickly answered when put to Syrian journalist Marwan Hisham.

“I would say that some people who live in certain countries where they are used to connecting to the Internet through fast WiFi and mobile data — they are ignorant about other methods of communication because they’ve never needed satellite internet or other techniques in their lives,” Hisham said. When Hisham was in eastern Aleppo last year, he said internet was actually faster than it is in the regime-held West due to the ubiquity of satellite connections, which the government bans. With repeaters placed around the city, a provider is able to blanket besieged neighborhoods with faster-than-legal WiFi that works even amid a bombing campaign.

“If my house was destroyed I could just go across the street and buy like 100 megabytes for 30 cents that will be enough for me to upload an HD video, not just tweet,” Hisham told ATTN:. “Almost every street is covered and there were hundreds of providers with thousands of repeaters in eastern Aleppo when I was there.”

Similar questions will continue to be raised, regardless of how past ones were answered, so long as there is a war in Syria. The victims of this conflict, as human beings, will continue to discover new ways to share their stories so long as they feel that they need to be heard, and that there’s still a chance someone’s listening: yesterday it was a diary, today it’s a post. The mundane horrors of war have left the world numb; the universal hope is that cynics may be moved by the innocent pleas of children. Policy is another debate — how, and can we even, answer those calls for help? — but it's one that requires acknowledging basic facts, like mass suffering in besieged and bombarded cities like Aleppo, and never forgetting the humanity and real pain felt by those so often treated as but shadowy pawns in a Washington panel discussion.

“The thing with Bana is that her mother is trying to show the suffering of children in Aleppo from a perspective that can have more of impact on Westerners,” Hisham said. “I can’t blame her for that. Who would?”