Rape on Campus is Widespread, But Not According to College Presidents

By:

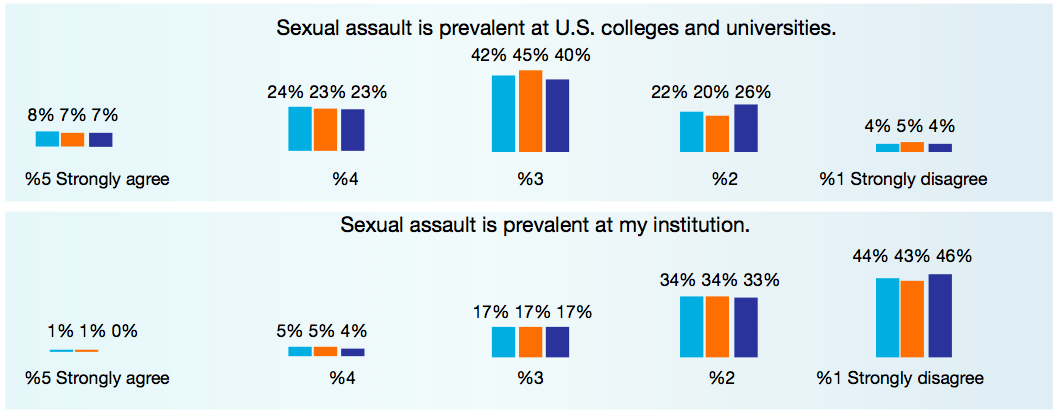

College sexual assault has been a widely discussed problem over the last year, but campus leaders aren't always willing to admit it affects their students. Inside Higher Ed’s fifth annual Survey of College and University Presidents reveals that while a third of college presidents acknowledge that campus sexual assault is prevalent at American colleges, only six percent think it's prevalent on their own campuses.

![]()

Via Inside Higher Ed

The great Rolling Stone disaster

The Inside Higher Ed survey results come at the same time Charlottesville, Va., police announced that they found no evidence of a brutal gang rape at the University of Virginia described last year in a Rolling Stone article.

“We’re not able to conclude to any substantive degree that an incident occurred at the Phi Kappa Psi fraternity house or any other fraternity house, for that matter,” Police Chief Timothy J. Longo said at a news conference Monday. “That doesn’t mean something terrible didn’t happen to [the victim] … we’re just not able to gather sufficient facts to determine what that is.”

The piece detailed the horrific aftermath of a UVA student's alleged sexual assault at a fraternity. The writer had honored the female student's request not to interview the reported attackers, and, consequently, the story was limited to the victim's side of the story. The story went viral, but readers quickly began to point out inconsistencies and question the integrity of the story, particularly the events surrounding the specific sexual assault described in the article. Rolling Stone went on to release a statement that the publication had been unwise to trust the young woman as much as it did, leading many to argue that the article posed significant setbacks for victims of rape.

How UVA responded to the student's initial claims and the article that followed

UVA's initial handling, as described by Rolling Stone, received wide criticism. Toward the end of the student's freshman year, she met with the dean to discuss declining academic performance and wound up confessing she'd been assaulted by fraternity brothers. The young girl was instructed to file a police report, submit a complaint with UVA, or speak to her attackers in front of the dean. When the story was first published, many readers argued that UVA didn't do enough to help the female student, prompting the university to temporarily suspend all Greek life activities as it conducted an investigation. UVA Greek life resumed at the beginning of January, but sororities and fraternities alike were required to adopt a set of new policies for increased student safety. The new rules involved more leadership training for sexual violence and alcohol awareness and sending safety recommendations to the university.

Are universities doing enough about campus sexual assault?

While the gang rape article was discredited and continues to face consequences in the media, the story itself described an ineffective investigatory process at UVA, raising the question of whether universities are taking sexual assault seriously. The above poll results from Inside Higher Ed are not adding to that confidence.

Scott Berkowitz, founder and president of the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), told ATTN: that the survey results reflect presidents being out of touch.

"My first reaction is that college presidents seem to be very out of step with the opinions of college students because we hear that overwhelmingly students feel like it's a big issue on the campus they are attending."

Berkowitz thinks that the spotlight on campus sexual assault has put universities on notice.

"The interesting contrast to the survey is that far more than six percent of campuses have started working aggressively to address sexual violence," he explained. "I think that one thing that's come out of all the press and legislative attention [on campus sexual assault] over the last year is that colleges that weren't doing anything before are being put on notice that they really need to work on that."

Despite university presidents being out of touch, many universities make sexual assault prevention and/or self-defense programs available to students, and often have sexual assault resource centers available for students. Becky Bell, an executive board member for the University of Arizona's pro-social behavior and bystander intervention program Step UP!, told ATTN: that organizations such as hers work tirelessly to educate men and women about how to prevent sexual assault and how to defend themselves. While there's no one quick silver bullet to stopping sexual assault on campus, self defense, education, and prevention programs are important tools.

"Step UP! Is being used by hundreds of schools and organizations, and we believe bystander intervention can be very effective in preventing any number of issues," Bell told ATTN:. Step UP!'s website states that the program "educates students to be proactive in helping others" and aims to raise awareness of how to help others in potentially dangerous situations.

What lawmakers are doing when universities are not acting soon enough.

Universities may also be concerned with reputation, and the negative image that could result from acknowledging sexual assault occurs on their campuses. A bad image could cost college presidents in enrollment numbers or donation dollars. But lawmakers in some states have decided to act, despite universities showing reluctance.

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo is pushing for legislation to mandate uniform sexual assault policies on private school campuses. The State University of New York system already has these rules in place, and Cuomo wants them at all colleges in New York state.

“The incentive, especially for private schools, is to handle the matter internally,” Cuomo said to the New York Daily News. “Why? Because the university doesn’t want the publicity in the newspaper of a rape. It’s not positive for the reputation of the school.”

Last year, California Gov. Jerry Brown passed what's commonly referred to as "Yes Means Yes," a law requiring state colleges and universities to take on "affirmative consent" policies, which requires students to receive a voluntary, conscious agreement from sexual partners. State Sen. Kevin de León came up with the measure after so many stories about college sexual assaults made news.

“As the father of a young college-age daughter, I was stunned, I was quite surprised when I read the statistic that 20 percent of young women have been sexually assaulted on a college campus," de León said to the Sacramento Bee last month. "These are our daughters, they are our sisters, they are our nieces."

The "Yes Means Yes" campaign also drew a fair amount of criticism, with some arguing that consensual sexual interactions might be considered sexual assault under this standard. One of the bill co-authors, for instance, said that affirmative consent means one of the parties must say the word "yes," otherwise it may not be a consensual interaction. Others were uncomfortable with the idea of shifting the burden of proof to the accused, who must prove there was consent or essentially prove they are not guilty.

This month, the Colorado House preliminarily approved a measure that would make colleges and universities provide nearby medical facilities so students could have sexual assault exams performed. The bill came forth after news reports surfaced that only one Colorado university provided rape kits on campus.

Sexual assault is a hard problem to solve.

One of the trickiest aspects of sexual assault is how difficult it is to prove, and that could be a main reason college presidents don't think it happens on their campuses. Many cases of sexual assault go unreported, and that skews the data we do have.

So if everyone came forward about sexual assault, would university presidents see this problem in their institutions? That's difficult to know because many of these cases come down to the great problem of "he said, she said." It's also possible for rape victims to have fuzzy memories of their traumatic experiences, which can lead to peculiarities in the retelling of events and cast doubt on the victim's claims. It's not unheard of for victims to commit suicide upon coming forward about their assaults. The trauma of sexual assault coupled with the stress of speaking out can be too much for some people, so many instances of assault aren't brought to the college president level.

With more politicians acting on this pervasive problem, will college presidents get on board and see that sexual assaults on campus are much more damaging than negative press?