5 Kinds of Junk Science Prosecutors Have Used to Send People to Prison

By:

If you've ever seen an episode of "Law & Order," you've probably learned that forensic evidence plays a crucial role in the criminal justice system. But some of the science used to convict people in actual U.S. courts of law may be junk science.

An upcoming report from the President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology took a look at several forms of forensic evidence and raises major questions about their validity, according to The Intercept.

U.S. Attorney General Loretta Lynch has already issued new restrictions and guidelines on the use of forensic science in trials.

AP/J. Scott Applewhite - apimages.com

AP/J. Scott Applewhite - apimages.com

The guidelines ban forensic examiners and prosecutors from using the words "reasonable scientific certainty" and "reasonable [forensic discipline] certainty" in testimony and reports. It also requires Department of Justice laboratories to post validation studies online and outlines a 16-part Code of Professional Responsibility for the Practice of Forensic Science.

These guidelines and the White House report may inspire policy shifts pertaining to the use of forensic evidence in criminal cases. But experts and advocates have long insisted that our criminal justice system has a junk science problem, as Aeon explained.

Here are five ways people have been convicted based on shoddy science.

1. Bite marks

The White House report's findings on bite mark analysis are particularly troubling, The Intercept reported.

The president's council questioned the fundamental claim that human bite marks are unique and the ability of examiners to accurately discern bite marks from other injuries.

"PCAST finds that bite mark analysis does not meet the scientific standards for foundational validity and is far from meeting such standards," the report said. "To the contrary, available scientific evidence strongly suggests that examiners cannot consistently agree on whether an injury is a human bite mark and cannot identify the source of [a] bite mark with reasonable accuracy."

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

At least 25 people whose convictions hinged on bite mark evidence have been exonerated since the year 2000, the Innocence Project reported.

Forensic dentists have pushed back against critiques of their research and practices over the years, including a damning 2009 report published by the National Academy of Sciences, The Intercept reported. The White House report is expected to be released later this month; it's unclear what — if any — policy shifts will result from its findings.

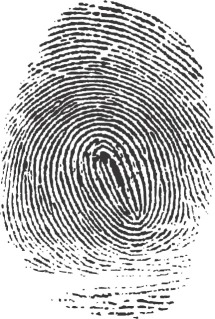

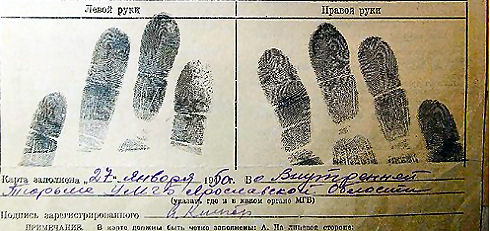

2. Fingerprint analysis

The president's council report also discussed fingerprint matching — a far more common form of forensic science than bite mark analysis.

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Reaching the conclusion that two prints are from the same person "gets a little fuzzy," Glenn Langenburg, a fingerprint examiner at the Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, told Science Magazine.

From Science Magazine:

"One study of 169 fingerprint examiners found 7.5 percent false negatives—in which examiners concluded that two prints from the same person came from different people—and 0.1 percent false positives, where two prints were incorrectly said to be from the same source. When some of the examiners were retested on some of the same prints after seven months, they repeated only about 90 percent of their exclusions and 89 percent of their individualizations."

Since the National Academy of Sciences published its 2009 report, parts of the forensic science community have wrestled with these inconsistencies and tried to develop statistical tools to explain margins of error in forensic comparisons.

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

The National Institute of Standards and Technology awarded $20 million in May 2015 to the Center for Statistics and Applications in Forensic Evidence — a group of legal and statistical experts — to create analytical tools to measure the accuracy of various forms of forensic evidence.

"I know some people think we are not going to be able to do this, [that] you cannot put a probability on some types of evidence," the center's director and Iowa State University statistician Alicia Carriquiry told Science Magazine in a March report. "And they may be right, but we need to try."

Carriquiry said that a reliable database would need to illustrate a "likelihood ratio." This would allow examiners to show how confident a match is by comparing it to matches between randomly selected fingerprints.

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

The president's council report also recommends telling jurors about studies on the accuracy of fingerprint matches alongside evidence.

blogspot/gavs-maria - flickr.com

blogspot/gavs-maria - flickr.com

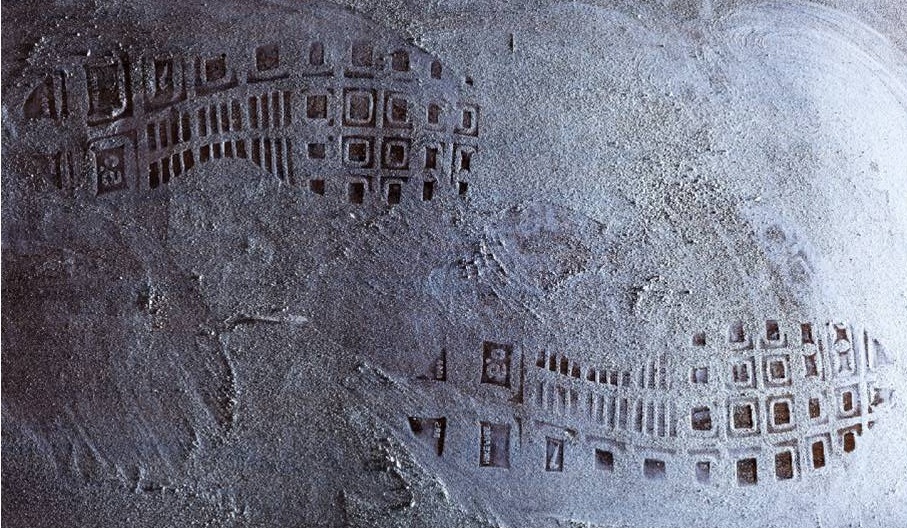

3. Shoe tread marks

Shoe tread patterns present similar issues to fingerprint comparisons.

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Wikimedia Commons - wikimedia.org

Examiners need to determine the relevance of various aspects of a shoe print: the brand, how worn it is, and if the shoe is damaged, Science Magazine reported.

An accurate shoe print database would require examiners to keep up with brand name and counterfeit shoe markets, as well as how shoe print patterns differ regionally, depending on terrain, forensic scientist Lesley Hammer told Science Magazine.

Charles Irvin Fain was exonerated in 2001 after serving almost 18 years on death row for a rape and murder that DNA analysis ultimately proved he did not commit. An FBI forensic examiner's shoe print comparison was central to his conviction, the Innocence Project said.

The president's council report concluded that no studies supported linking shoe treads to a suspect's footwear based on "randomly acquired characteristics" — i.e., the wear-and-tear to a shoe, the Intercept reported.

4. Hair samples

Hair sample comparisons have also come under scrutiny in recent years, as The New York Times editorial board explained in 2015.

The national academy's 2009 report said that there was "no scientific support" and "no uniform standards" for the use of hair sample comparisons.

A judge vacated the murder conviction of Santae Tribble in 2012 because of a faulty hair sample. The prosecution claimed that the odds a hair did not belong to Tribble were 10 million to one, the Times reported. DNA testing ultimately revealed that the hair samples didn't match and that one of the strands belonged to a dog.

Flickr/RD_Elsie - flickr.com

Flickr/RD_Elsie - flickr.com

Tribble's case led the FBI to review 2,500 convictions. The first part of the review, reported by The Washington Post, found that hair sample analysts from the FBI testified wrongly for the prosecution in 257 out of 269 cases.

5. Firearm analysis

The president's council report found that linking bullets at the scene of a crime to a specific firearm is possible in certain cases, but that this form of forensic analysis is also in need of serious reform.

snowjackal / Wikimedia Commons - wikipedia.org

snowjackal / Wikimedia Commons - wikipedia.org

The council asserted that the practice is under-researched and too subjective.

The 2009 National Academy of Sciences report found that firearm analysis also needs to be studied more extensively to account for variations between individual firearms, but that the method can be helpful in terms of narrowing a pool of suspects.

The problem of junk science in courts also ties into how evidence is presented to and perceived by juries.

ATTN: has reported previously that legal experts worry that exposure to TV shows such as "CSI: Crime Scene Investigation" and "Law & Order" has significantly changed what juries expect from forensic experts. This has been aptly termed "The CSI Effect."

Felony trial judge Donald Shelton asserted in the NIJ journal that he believed this phenomenon sometimes led experts to perform irrelevant tests to cater to jury expectations.

"They will perform scientific tests and present evidence of that to the jury," Shelton told NPR. "Even if the results don't show guilt or innocence either way, just to show the jury that they did it."