American Inmates Are Leaving Prison With These Incurable Diseases

By:

Prisons are cesspools for infectious diseases and basic safeguards that could prevent their spread are frequently unavailable, The Atlantic's James Hamblin writes. The failure to provide preventative health care services to America's prison population ultimately puts everyone at risk.

Flickr/Travis Wise - flic.kr

Flickr/Travis Wise - flic.kr

It comes as little surprise that not all prisons are meeting international health care standards.

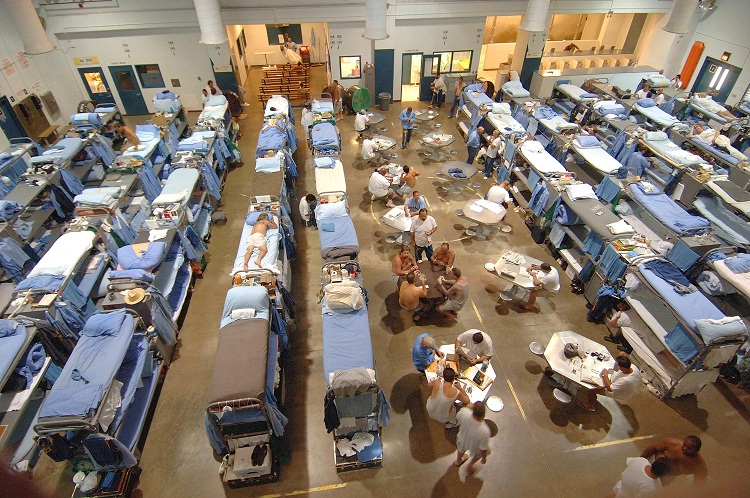

Prisons in the U.S. are often underfunded and overcrowded, which puts a strain on already limited resources. But the extent to which this problem is driving the spread of infectious diseases such as HIV, hepatitis C, and tuberculosis hadn't been extensively studied before a team of researchers at Johns Hopkins University rose to the task.

Researchers analyzed data on rates of infectious diseases in prisons globally and developed a model to estimate how these diseases spread following a prisoner's release. After reviewing six recommendations from the World Health Organization on disease prevention in prisons, researchers then compared how diseases spread in countries that have adopted the recommendations with those that have not.

The team published their findings in The Lancet medical journal last week, concluding that the prison health crisis and governments who refuse to take action "constitute violations of human rights to be free of discrimination and cruel and inhuman treatment, to due process of law, and to health." There are ways to prevent the spread of disease in prison — by offering needle-exchange programs, condoms, and opioid substitution therapy, for example — but those services are underutilized to a dangerous degree, the researchers argue.

Wikimedia/California Department of Corrections - wikimedia.org

Wikimedia/California Department of Corrections - wikimedia.org

"The penal system remains a source of diseases that spread among prisoners at rates far exceeding those in the communities from which they came," Hamblin reports. "Of more than 10 million incarcerated people in the U.S. alone, 4 percent have HIV, 15 percent have hepatitis C, and 3 percent have active tuberculosis. These diseases are part of our criminal justice system, then, metered out and sanctioned implicitly by the state."

The problem starts at the prison, but it definitely doesn't end there.

Prisons are basically incubators of disease, and it's only when an infected prisoner is released — often without adequate access to health services — that the problem unravels. If a person with HIV leaves prison, where they were receiving antiviral medication, and then can't find a health provider to continue the treatment right away, then the virus returns with a vengeance.

AP/David Goldman - apimages.com

AP/David Goldman - apimages.com

"Those people are infectious again, and often highly so," Hamblin writes. "That creates a serious risk for their sexual partners, and anyone with whom they may share needles."

In recent years, there's been an international push to increase protections for prisoners — including the adoption of a United Nations resolution known as the Mandela Rules, which require prisons to provide prisoners with "adequate food, sanitation, ventilation," and protection from violence. But the U.S. still trails behind other countries such as Norway in terms of guaranteeing healthcare and rehabilitative services for prisoners, as ATTN: previously reported.

Hamblin continues:

"So an approach to infectious diseases must involve reform in criminal law, toward justice systems that do not treat substance abuse with imprisonment. For people who do make it to prison, care of infectious diseases is not care if it does not continue upon leaving. These policies will come from an emphasis on the penal system as a tool of rehabilitation, and an institution where human rights demand protection."