Paying For College Is Now Harder Than Paying Off A Home

By:

The debate around our country’s student loan crisis and how to fix it has officially reached a fever pitch. Last week, the New York Fed made an alarming discovery amid relatively bright news on American debt: We’re having a harder time paying off our student loans than we are paying for our homes. This comes as Debt Collective - an offshoot of the Occupy-born organization Rolling Jubilee - answered the rising college cost emergency on Feb. 23 by calling for a student “debt strike.” Organizers report that this action is the first of its kind in US history. Initiated by the "Corinthian 15," the effort will initially target for-profit colleges according to Debt Collective, with a first wave of students refusing to repay their loans and asking for the Dept. of Education to cancel debts coming from Corinthian Colleges.

I can see the comments now, like the one below from a recent New York Times story. If you took out the loans, that's your problem:

But what if the system is rigged in favor of corporate welfare, for-profit education, and Wall Street banks?

Why paying off a college education has become more of a struggle for the average person than paying off a house.

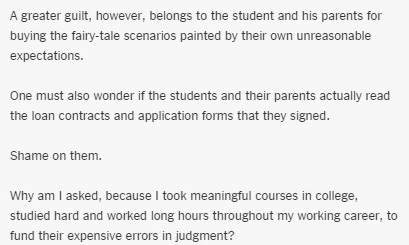

According to the Fed, delinquency rates for credit cards, mortgages, auto loans, and money borrowed against home equity peaked during the Great Recession, and all categories have fallen during the economic recovery. However, student loan delinquencies and defaults surged in 2012 - and have yet to stop.

More frightening, Fed data suggested that outcomes worsen over time. While most studies look at loan repayment over two to three years, by the nine year mark the Fed predicts an average 25 percent default rate.

Perversely, while attempting to make good on the American Dream, educational borrowers actually put their future at increased economic risk compared to other kinds of debt. Except in rare cases, you cannot discharge your student loan debt through bankruptcy. Private loan makers are also notoriously inflexible with borrowers that have fallen on hard times, often driving them into default. Couple debt that can follow you for the rest of your life with income potential that does not keep pace with degree program costs - earn just $40,000 a year and you’ve already landed yourself in the top 23 percent of Millennials - and you have a recipe for hardship.

(Note, we’re only talking about existing homeowners here. Studies suggest that many Millennials may defer real estate purchases and raising children due to student loan debt. The jury is still out on the impact that delaying these steps will have as our generation ages.)

This isn’t an isolated problem.

Student loans made up the smallest portion of household debt until 2009. Now, U.S. educational borrowing amounts to $1.16 trillion. This amount has been ballooning for years, surpassing total credit card debt almost five years ago - and jumping $77 billion in the last year alone. Nearly 1-in-5 households are impacted by student loans. That’s almost a quarter of the United States.

How did we get here? To answer that, we’ll have to dig deeper into state recessionary cuts.

Since the middle of the recession, states have protected their budgets by steadily divesting from their public colleges and universities. In California, which still provides the fourth highest need-based aid per student in the country, state higher education budgets have been slashed by 21 percent over the last six years. Meanwhile, cuts have topped over 30 percent in six states, shifting the burden heavily toward college-bound students and their families as colleges raise tuition to make up for the lost state funding.

Although many states began to restore some cuts to higher ed funding in 2014, 48 states are still spending less per student than they did pre-Recession. And against logic, eight states are actually still whittling away at college funding according to the Center on Budget & Policy Priorities. (Obviously, investing in a highly educated workforce to meet 21st century needs is overrated anyway. The governors of Illinois, Oklahoma, and Kansas certainly agree. ) In other words, state budgets have been balanced on the backs of America’s students and their families.

Sadly, the federal picture is actually worse.

No one was surprised when Congressman Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) proposed freezing Pell grants at $5,730 for 10 years in Apr. 2014. (These are the funds that help some of the least economically advantaged students attend college.) That measure may not have passed, but do you remember last December when Senate Democrats passed a spending package that dealt with a surplus in the Pell program by cutting $303 million rather than giving it to students?

These deep cuts more than five years after the Great Recession speak for themselves. Clearly, almost no one sides with students.

Adding to the unfairness, students also increasingly need a college education - the same education that they’re unlikely to successfully pay off - in order to get ahead in our modern economy.

Millennial degree-holders earned $17,500 more annually than those in the same age group with only a high school diploma. As Gint Aras smartly pointed out, the “path to earning a living wage isn’t as simple as ‘training in the vocations.’”

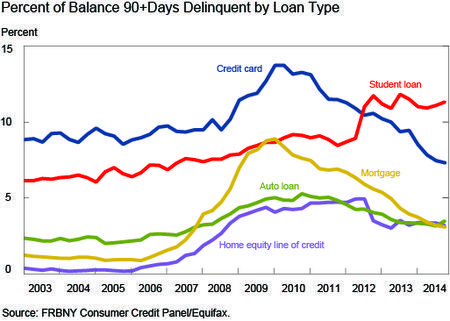

We’re in a trap that looks like the modern indentured servitude. While the holder of your debt has been uncoupled from your employer, the interwoven economic system still holds the keys to the kingdom. (Think about your credit score and its connection to your employability, for instance.) And even if you manage to pay your student debt off quickly, the costs by the time Millennials reach retirement can be staggering.

I was certainly disheartened to see the almost $400,000 loss at retirement that The New York Times uncovered last year. Because I’ve done just that - working two to five jobs simultaneously over the last seven years to pay down my student loans rather than saving.

Obviously, my situation could be worse; I’ve bucked the default trend. But making it through the gauntlet of substantial college debt shouldn’t be a matter of luck - and we definitely shouldn’t swallow the pill that this is fair or normal.